Common HNMR Patterns

In this tutorial I want to walk you through the common 1H NMR patterns you absolutely want to recognize before an exam. These patterns show up constantly in homework, practice sets and tests, and if you can spot them quickly, you can solve spectra much faster and with far more confidence.

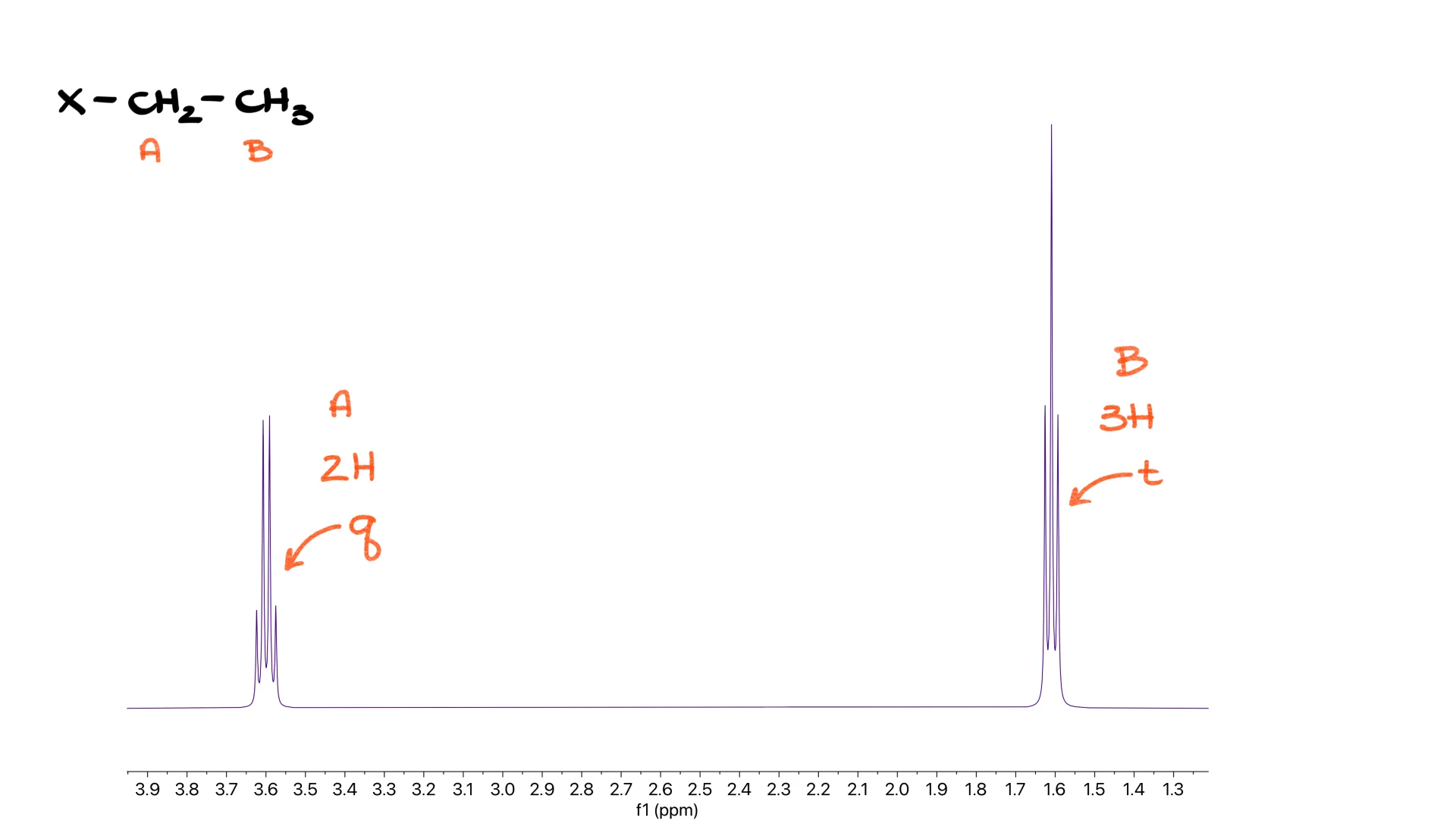

Ethyl Group

Without any delay, let’s start with the ethyl group.

An ethyl group always produces two signals. You see a quartet for the CH2 portion and a triplet for the CH3 portion. If we label the protons A and B, the A protons are the two hydrogens in the quartet, and the B protons are the three hydrogens in the triplet. You have probably seen this one many times.

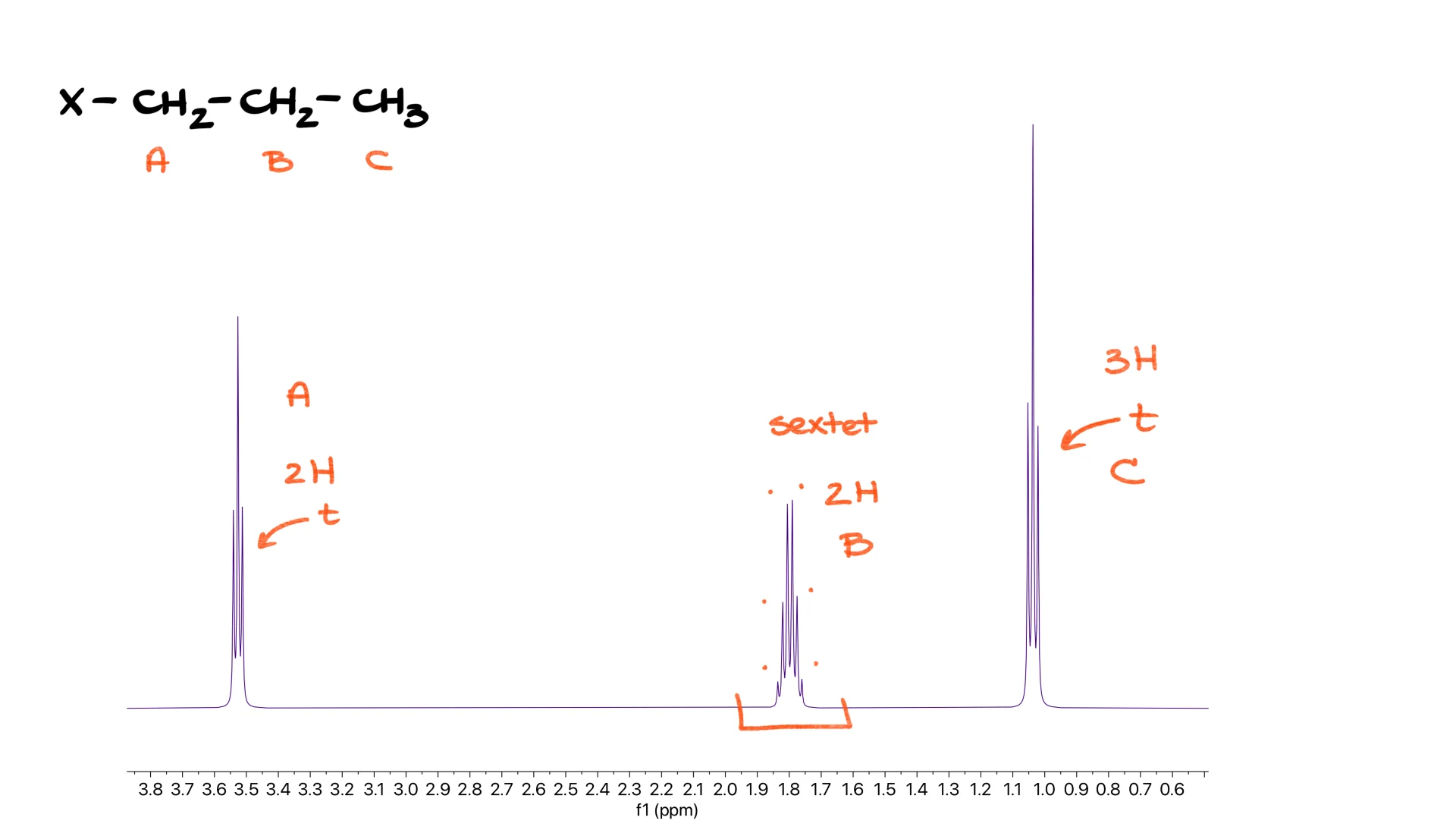

Propyl Group

The next classic pattern is the propyl group.

Here we find three signals. First, a triplet from the terminal CH3, then a large multiplet in the middle that is actually a sextet representing the central CH2, and finally another triplet from the second CH2. Labeling the protons A, B and C gives A as the first triplet, B as the sextet and C as the final triplet.

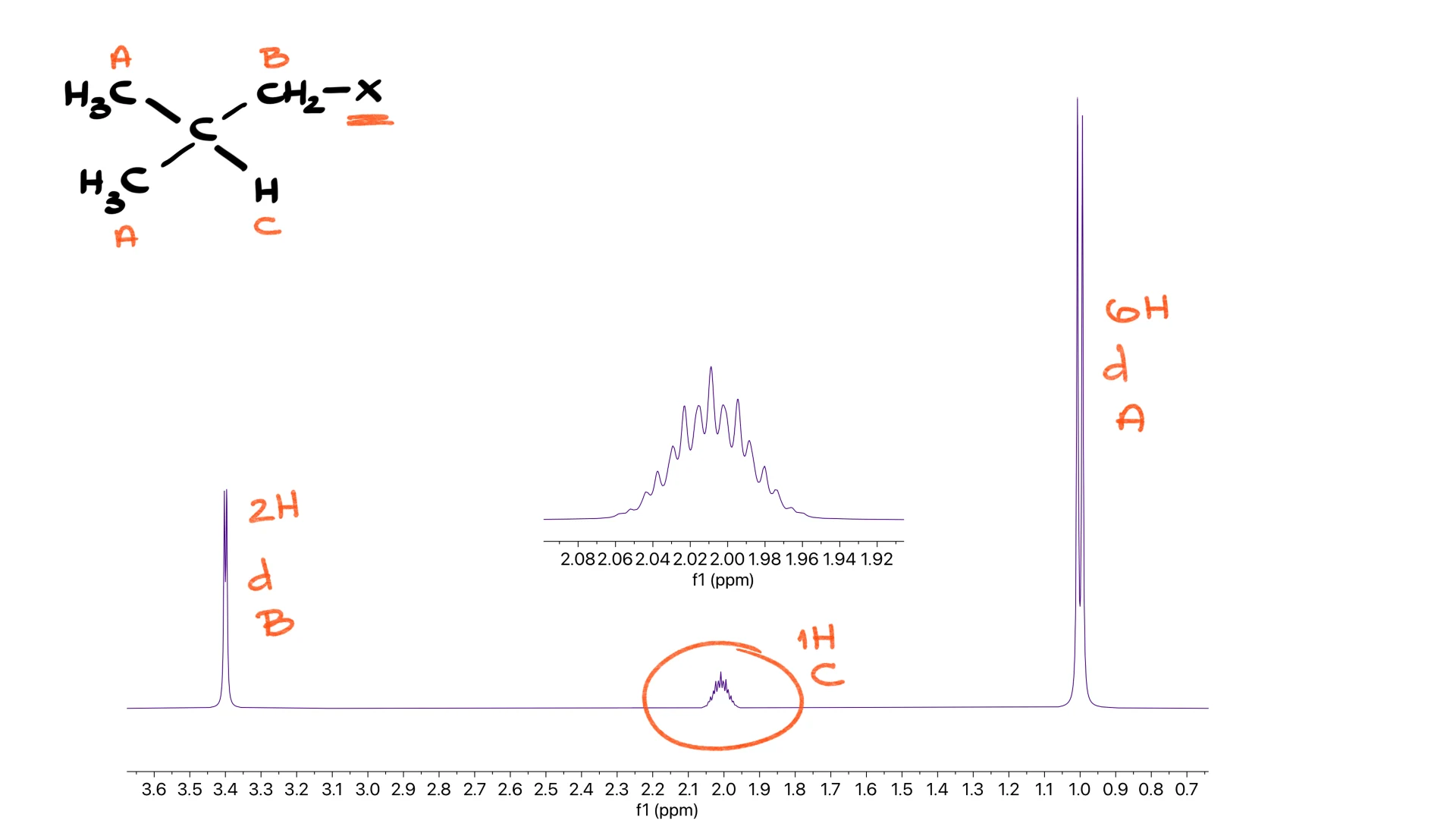

Isopropyl Group

Another everyday pattern is the isopropyl group.

The standout feature here is a doublet that corresponds to six hydrogens, plus a complex multiplet that corresponds to one hydrogen. That multiplet is usually a septet, though depending on instrument quality it may not be clearly resolved and can look messy. Still, the combination of a six-hydrogen doublet and a one-hydrogen multiplet is unmistakable.

Isobutyl Group

A slightly more chaotic pattern appears in isobutyl groups.

You see a doublet representing two hydrogens, another doublet representing six hydrogens and a complex multiplet in the middle representing a single hydrogen. This middle signal ideally would be a nonet because that hydrogen sits next to eight neighbors, but real spectra often distort it into a general multiplet. The pattern is still easy to recognize.

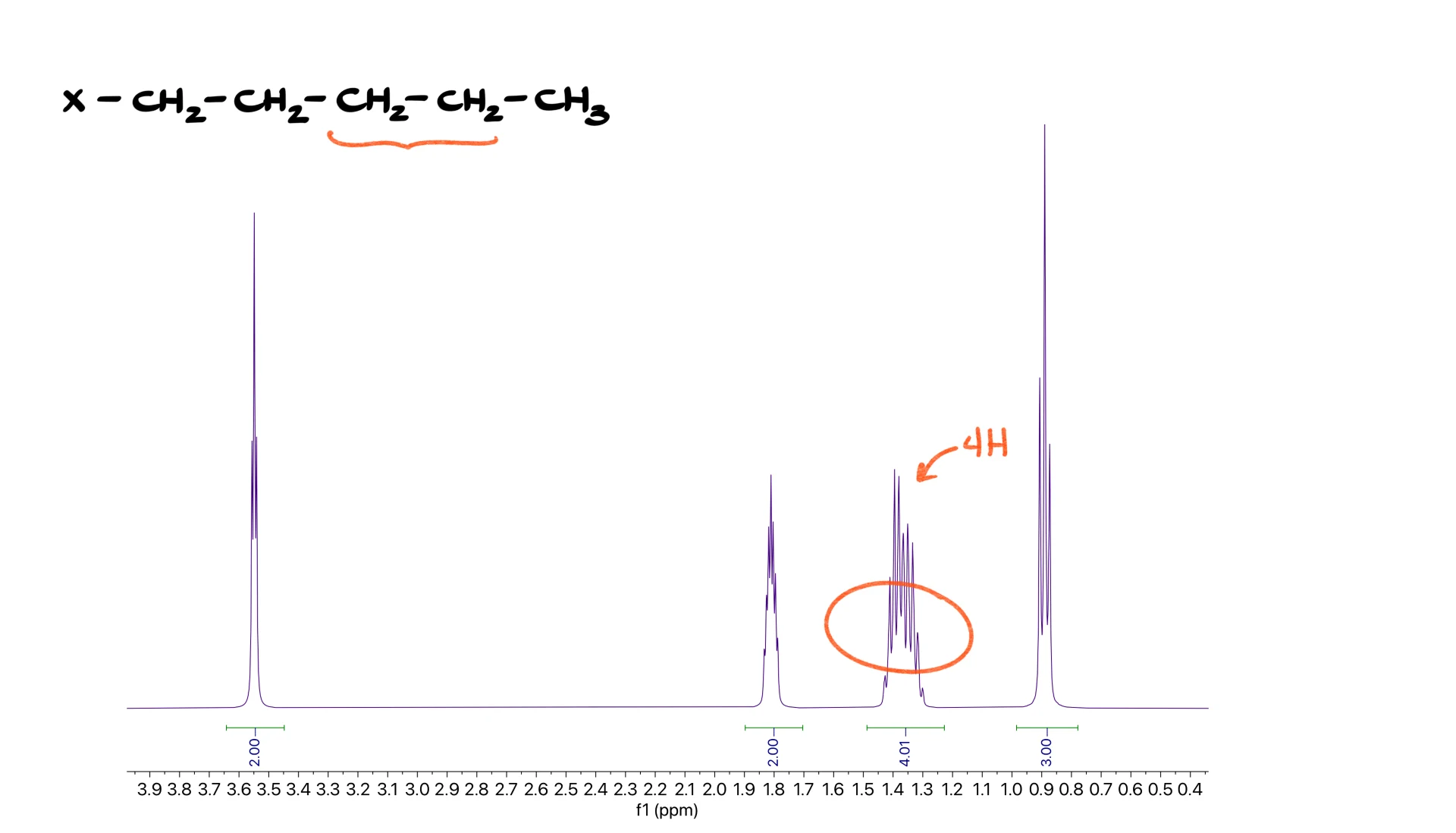

Long Chain “Forest”

Longer chains introduce what I like to call a forest.

In the aliphatic region, usually between 1.0 and 1.5 ppm, CH2 groups overlap to produce a messy band of peaks. In a pentyl chain, for instance, the middle CH2 groups overlap heavily, giving a multiplet that corresponds to two signals of two hydrogens each. Whenever you see this forest, it usually means a long aliphatic chain.

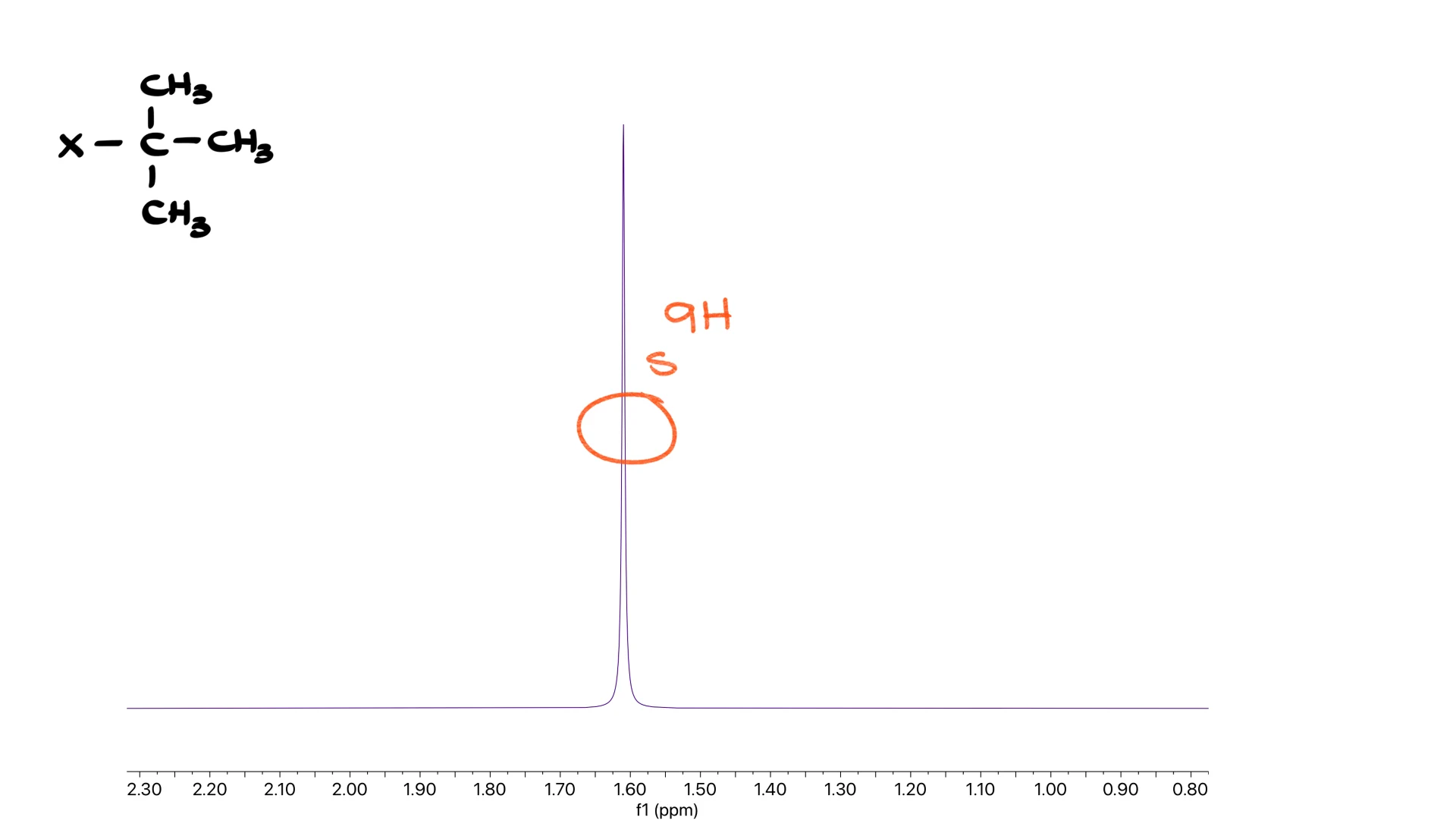

Tert-Butyl Group

Before moving on, here is the classic low-hanging fruit: the tert-butyl group.

One giant singlet of nine hydrogens is the tell-tale signature.

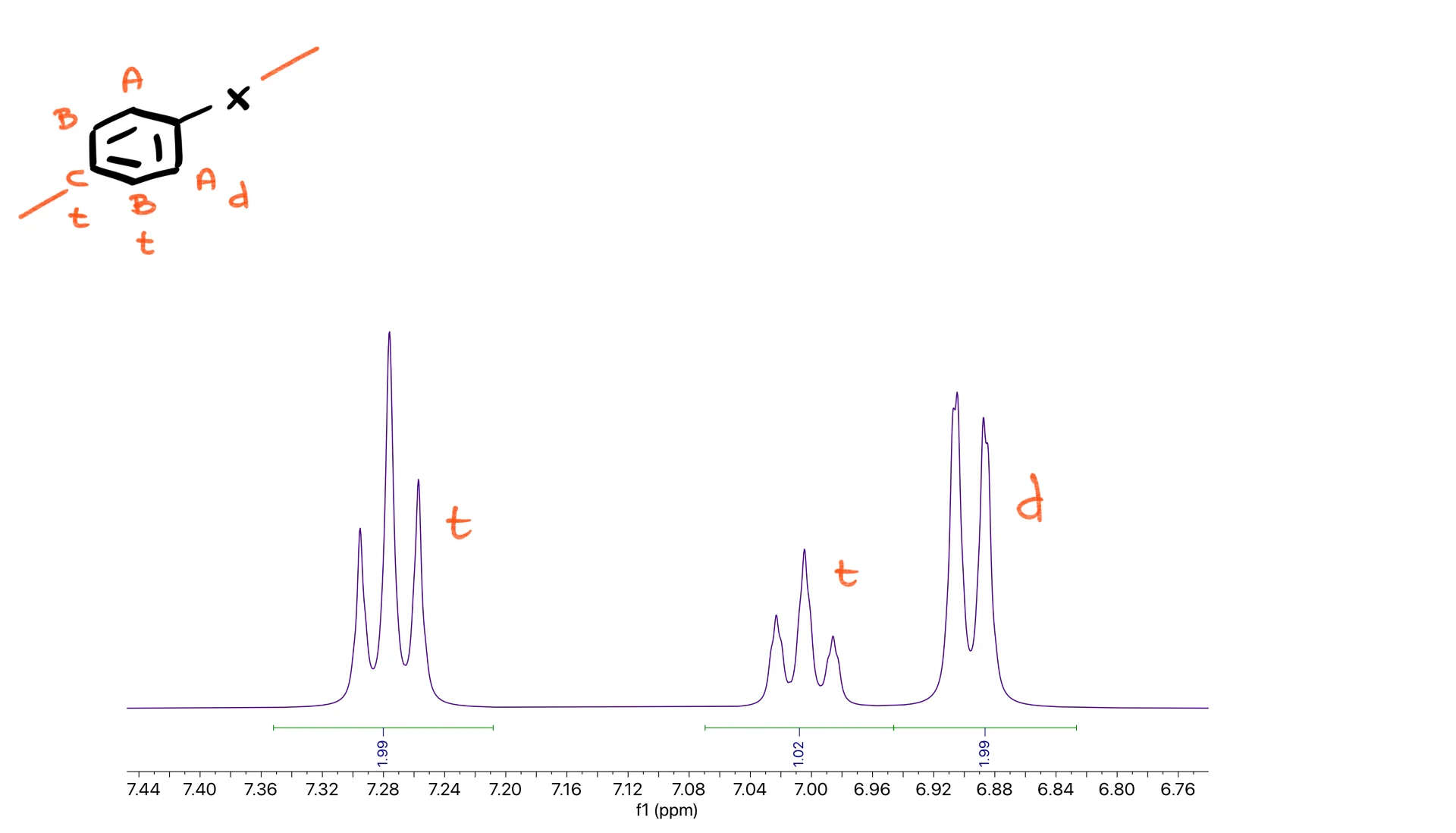

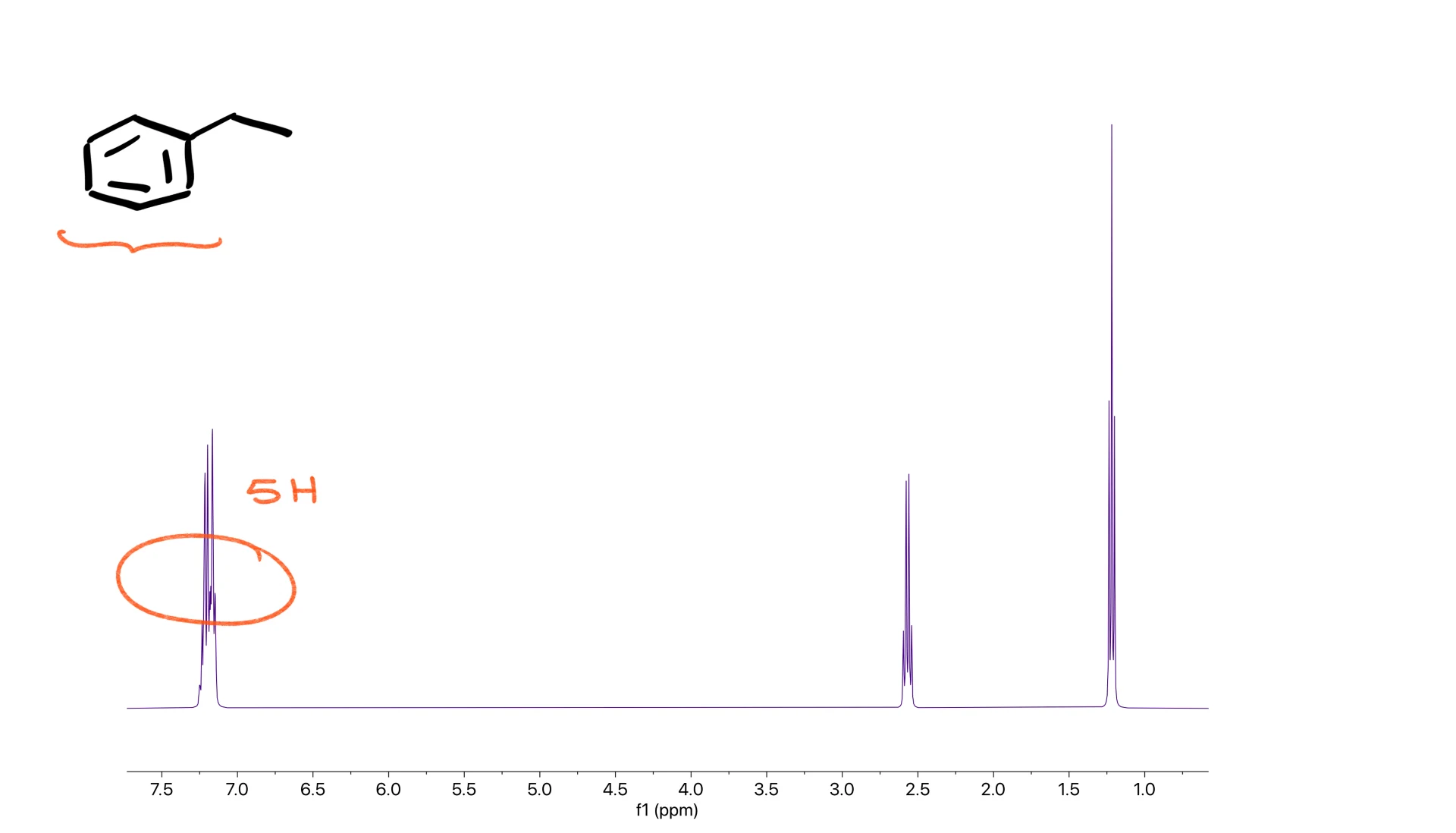

Phenyl RIng

Now let’s explore aromatic patterns. A bare benzene ring has an internal plane of symmetry, so you expect three signals: two triplets and one doublet.

The triplets correspond to the B and C protons, and the doublet corresponds to the A protons. In a clean spectrum these appear as nicely separated peaks.

However, real spectra of simple monosubstituted benzenes often collapse into a messy multiplet because the chemical shifts are too close. Sometimes the entire aromatic region collapses into a large signal integrating for five hydrogens. That is still just the expected pattern for a monosubstituted benzene.

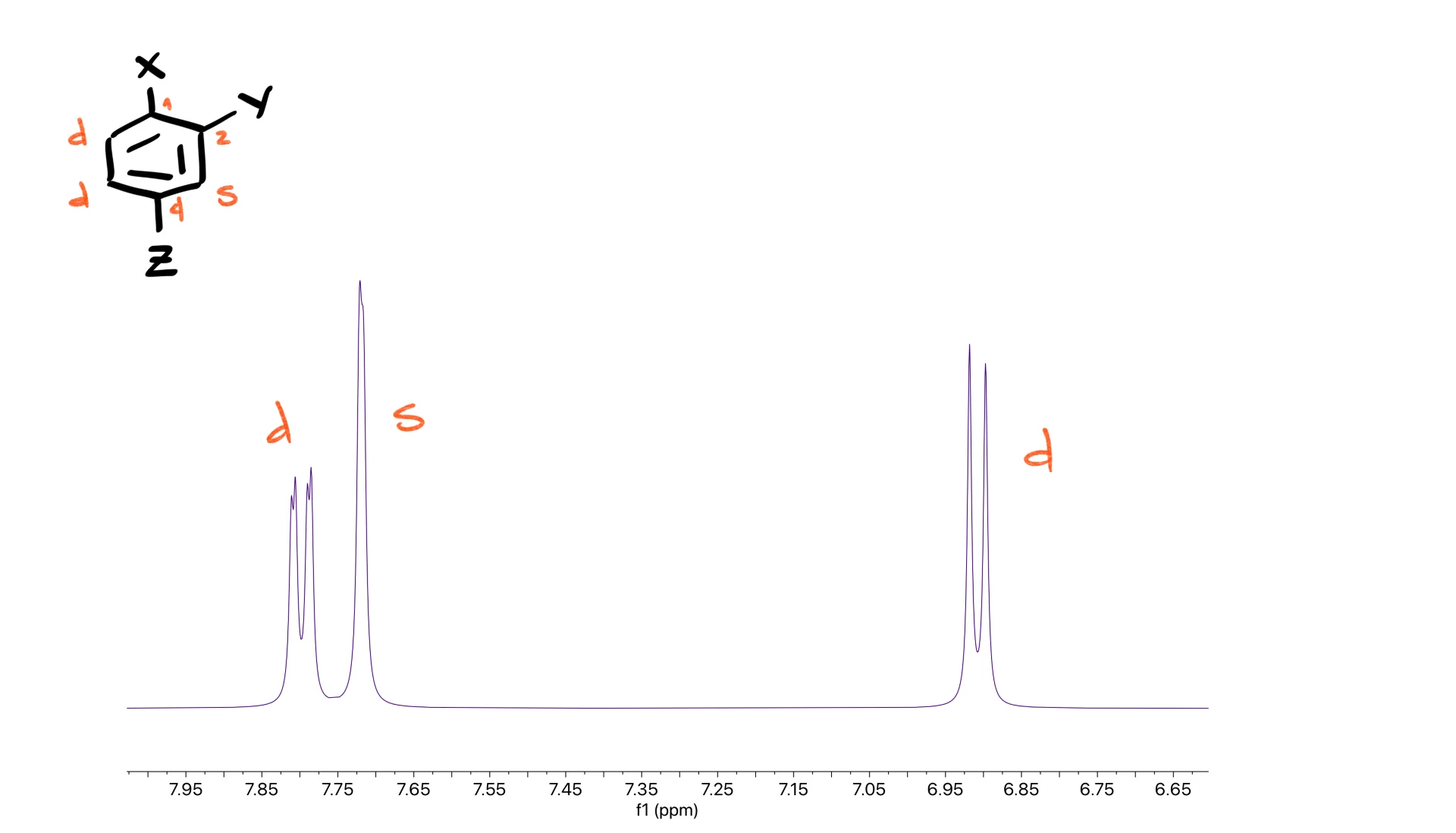

Di-Substituted Aromatic Rings

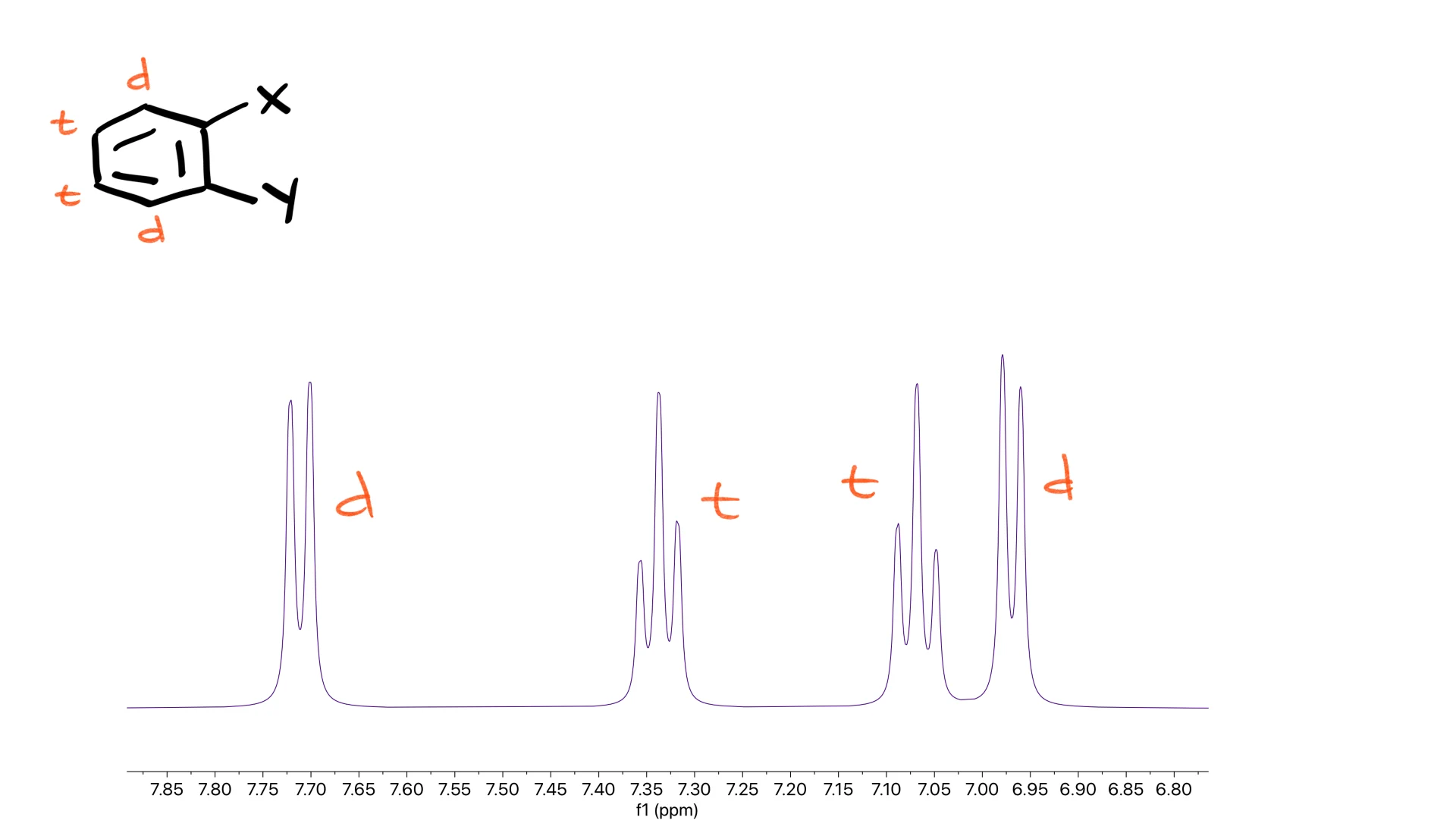

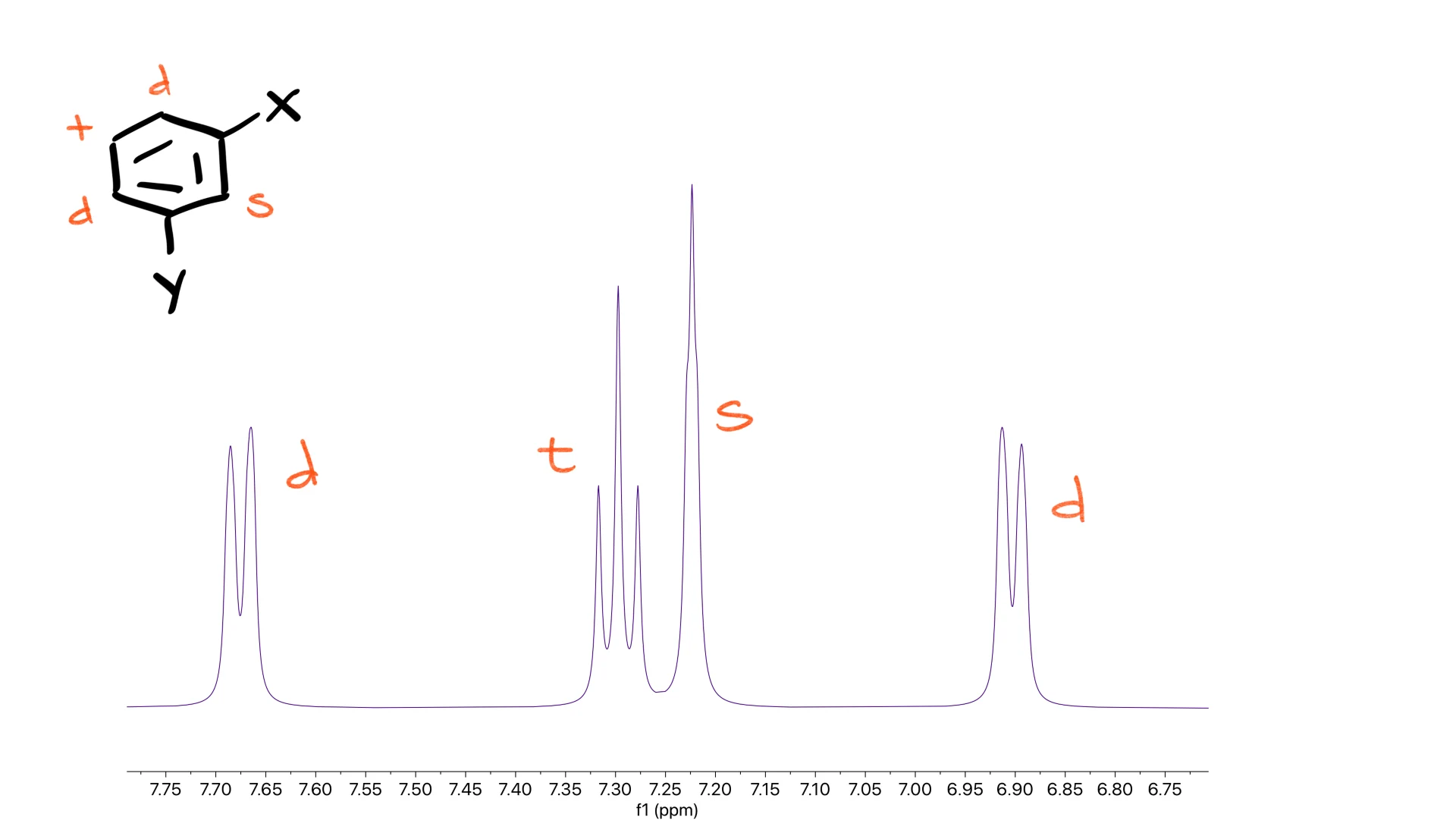

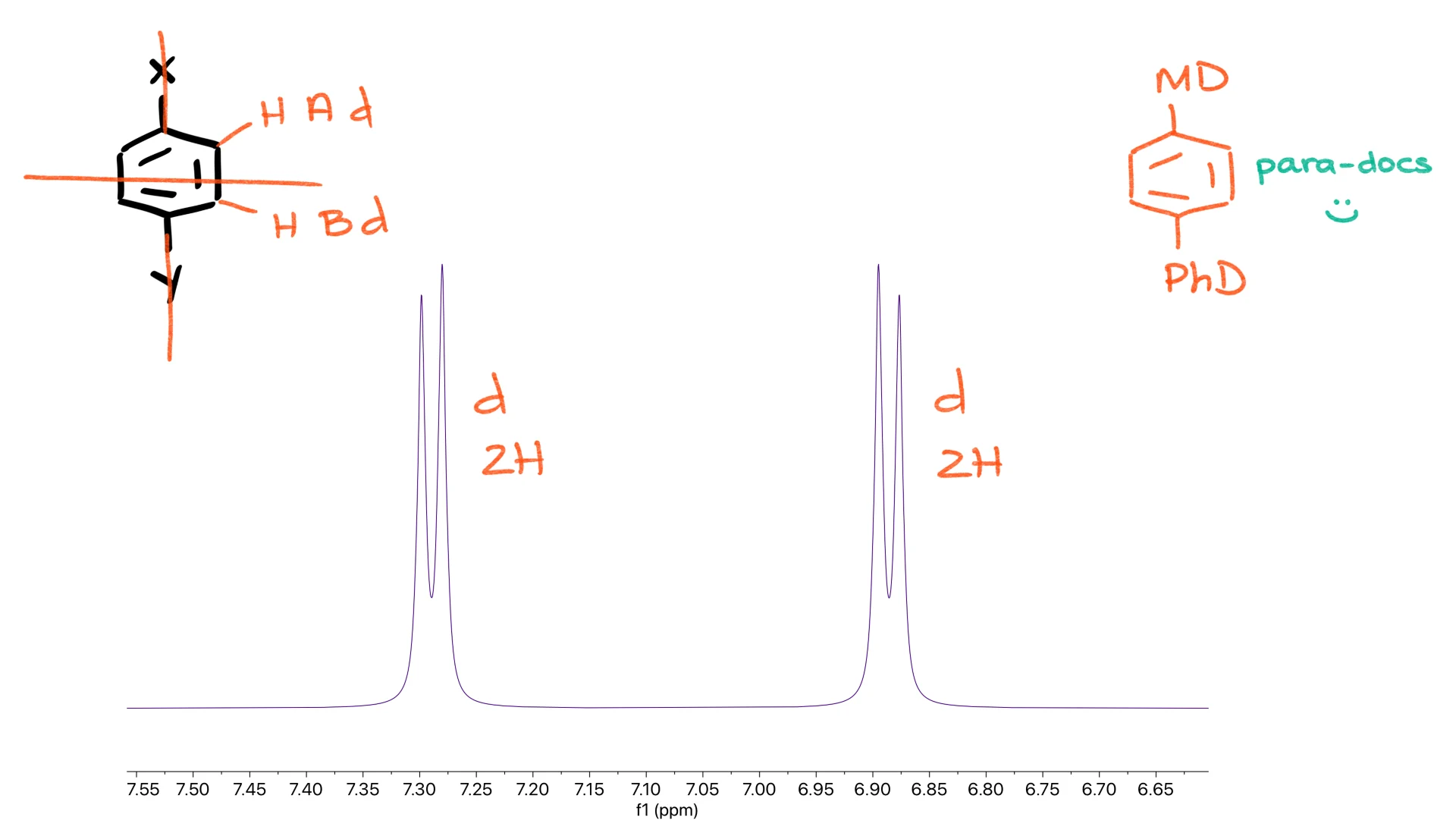

Disubstituted rings are extremely common on exams.

For an ortho-disubstituted aromatic ring, all four aromatic hydrogens are in unique environments, so you should expect two doublets and two triplets.

For a meta-disubstituted ring, the pattern becomes a singlet, two doublets and a triplet.

The most common pattern of all is the para-disubstituted ring. Because it has both vertical and horizontal planes of symmetry, only two sets of hydrogens exist, and you get a pair of doublets, each integrating for two hydrogens.

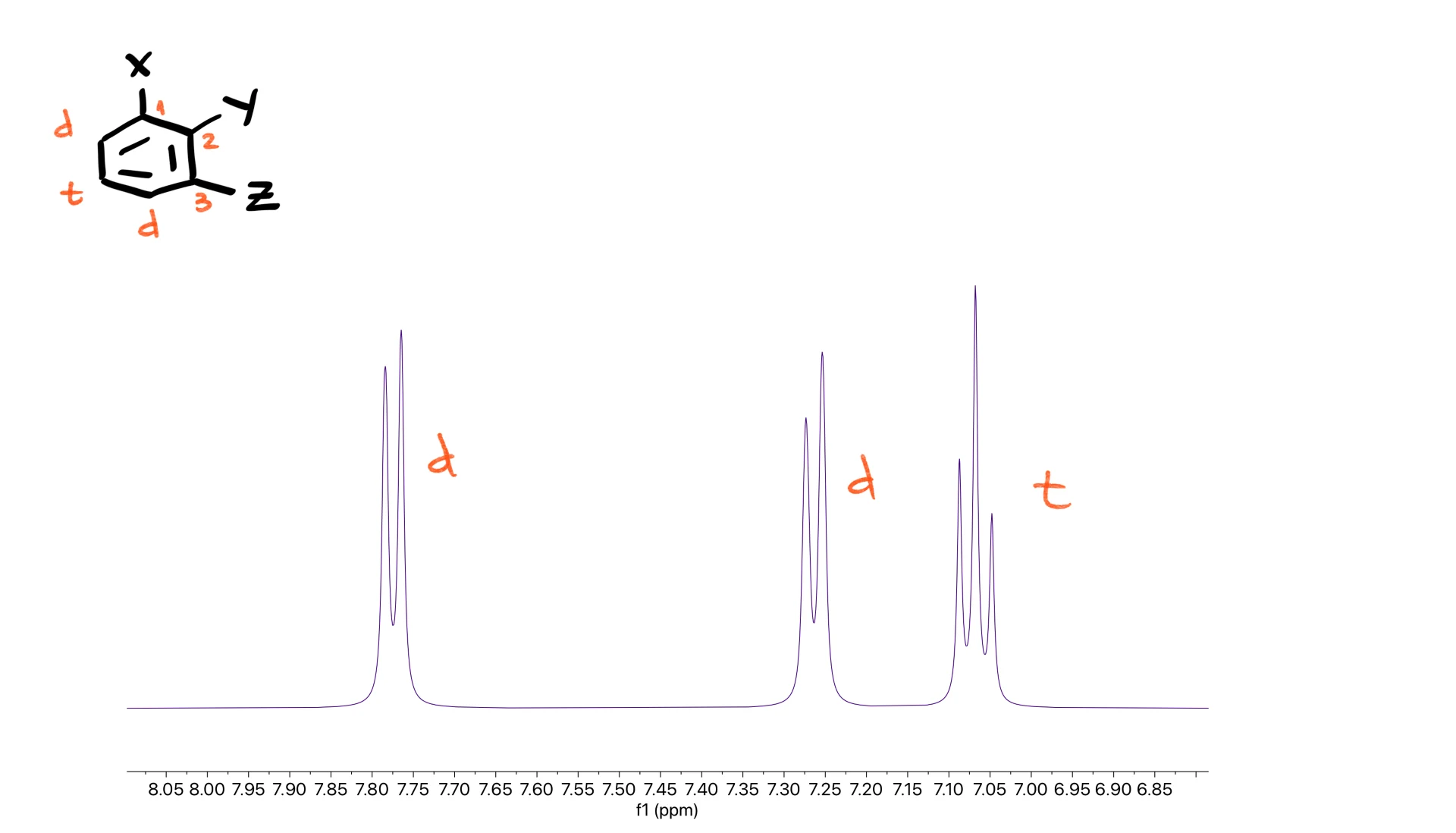

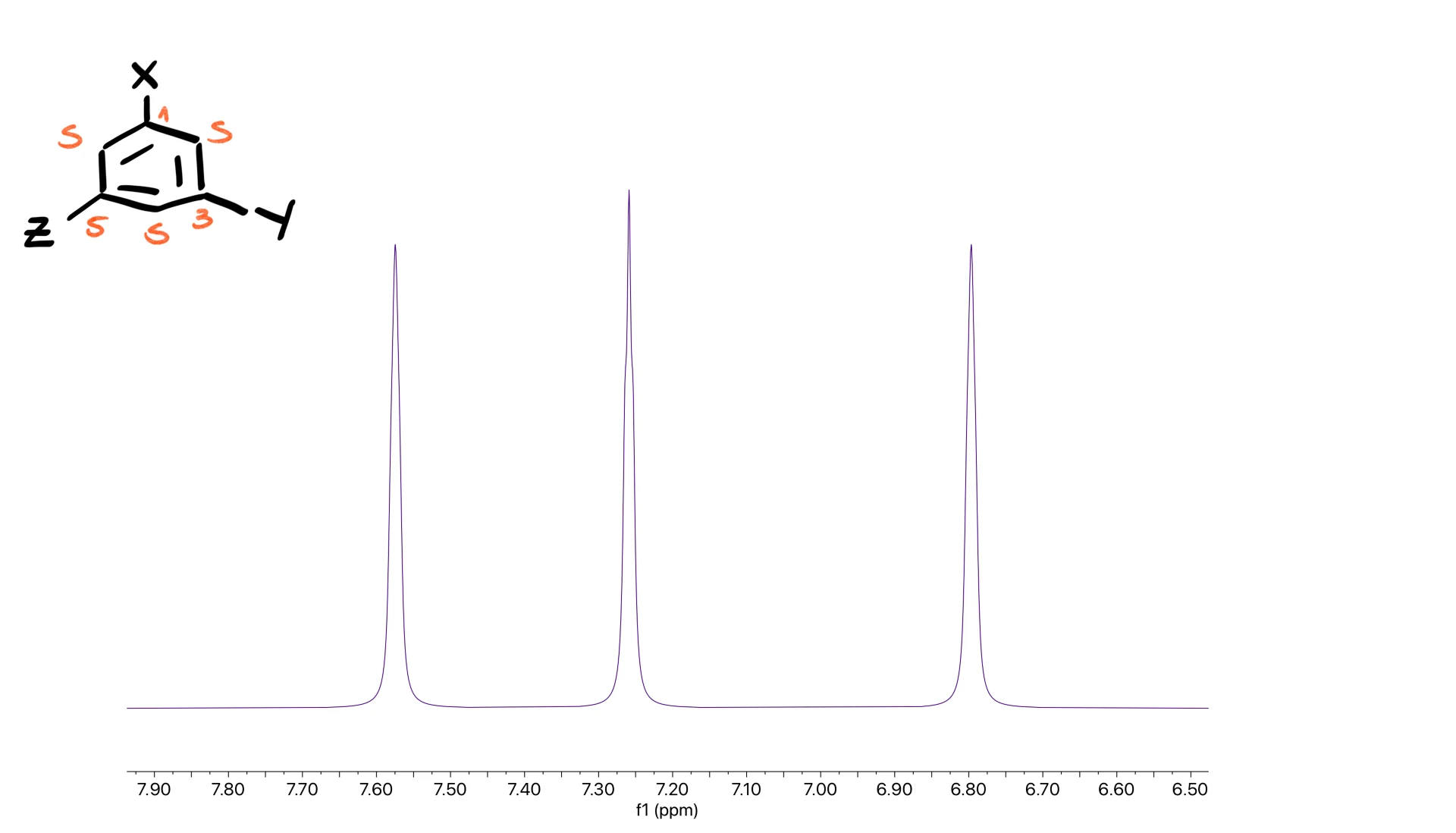

Tri-Substituted Aromatic Rings

Tri-substituted rings appear less often, but you still want to recognize them.

For substitution at the 1,2,3-positions you expect a doublet, another doublet and a triplet.

For the 1,2,4-pattern you expect a singlet and two doublets.

For the 1,3,5-pattern you expect three clear singlets, which is the easiest tri-substituted pattern to identify.

A small disclaimer: the spectra I showed here are clean textbook examples. Real spectra can be less tidy, but within the normal difficulty range of an introductory course, the patterns tend to appear clearly enough that you can identify them without too much trouble.

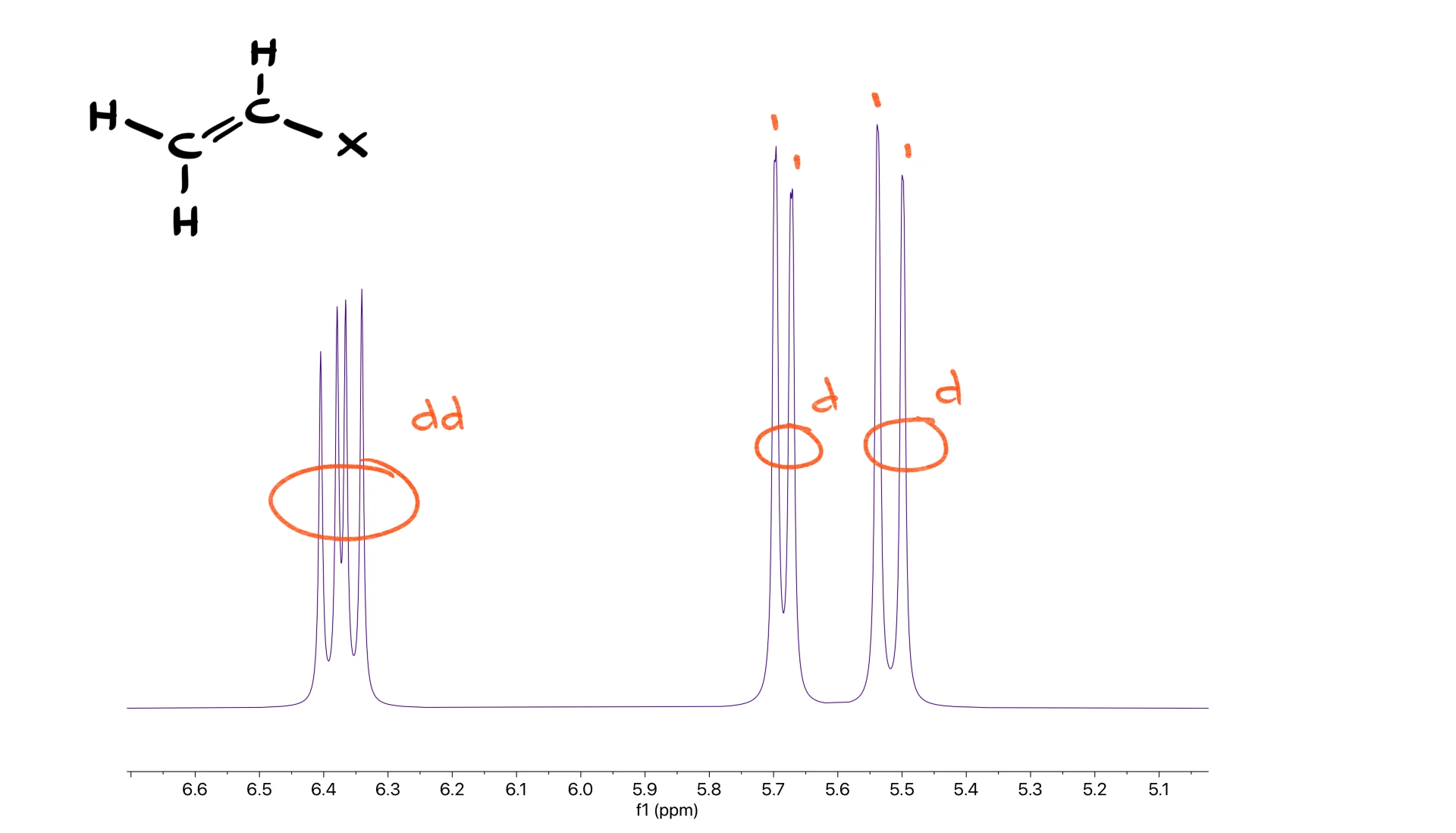

Vinyl Group

Before wrapping up, let’s look at one more useful pattern: the vinyl group.

In the region where double-bond hydrogens appear, usually between 5 and 7 ppm, a vinyl system gives a signal with four peaks and two doublets. The four-peak signal looks like a quartet, but it is actually a doublet of doublets. The key identifier is that the two doublets have different coupling constants, so one doublet is wider than the other. Whenever you see this combination, you are looking at a vinyl fragment.

If you learn to spot these patterns quickly, you will move through NMR problems much faster and with far less stress on exams.