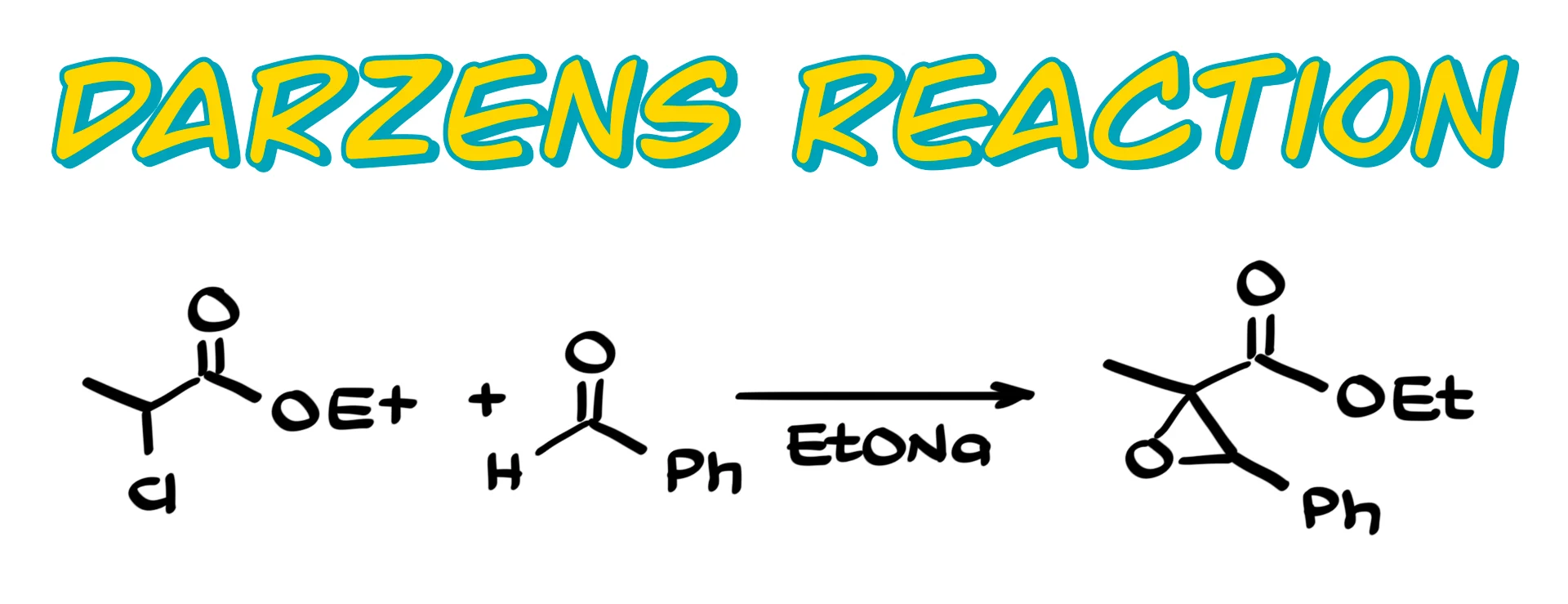

Darzens Reaction

In this tutorial I want to walk you through a very interesting transformation known as the Darzens reaction.

This reaction converts an aldehyde or a ketone into an epoxide by reacting it with an α-halogenated ester, although other α-halogenated carbonyls can work as well.

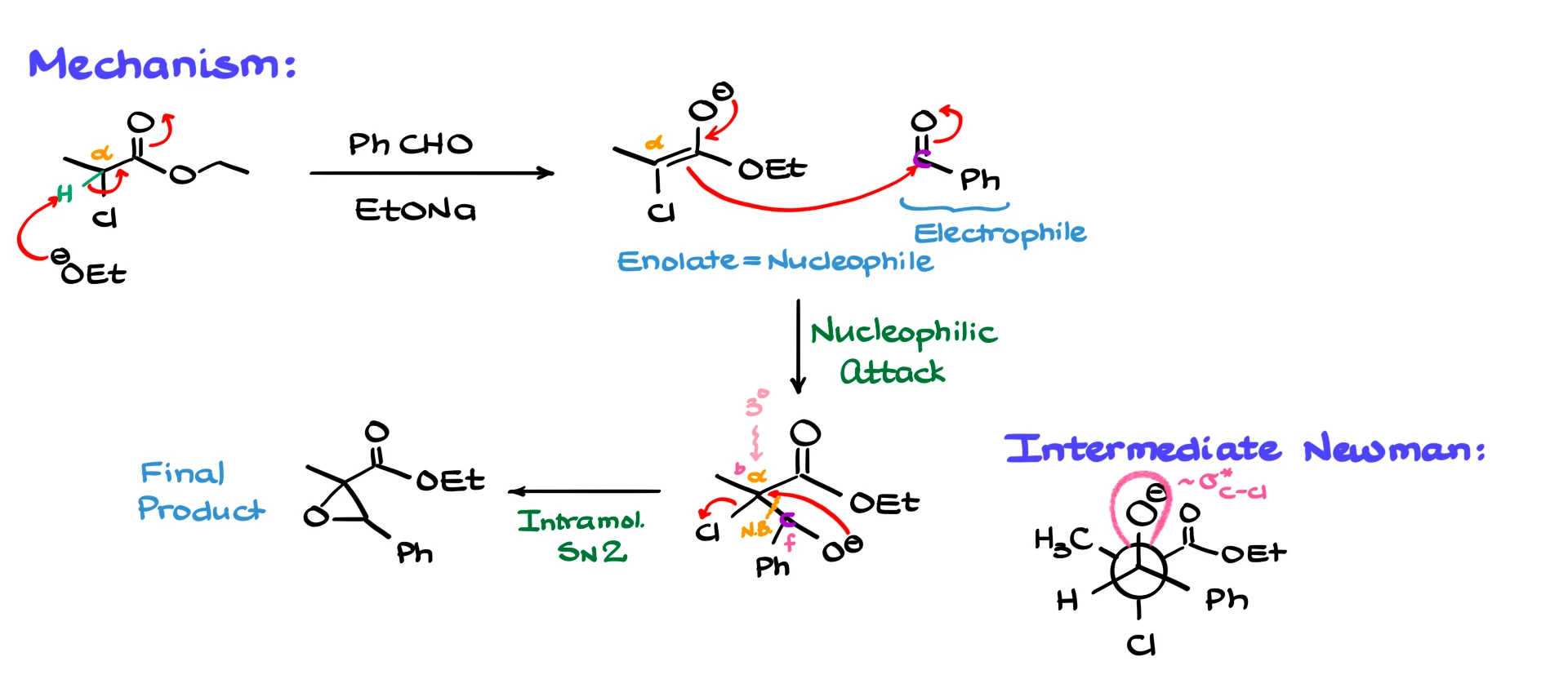

Mechanism

I will start by redrawing the starting materials.

The first event in the mechanism is the enolization of the α-carbon next to the carbonyl in the ester. The proton on that α-position is fairly acidic because of the chlorine attached to that same carbon. The ethoxide base easily removes that proton, giving the corresponding enolate.

Enolates are strong nucleophiles, and in our reaction mixture we also have an aldehyde, which is a very good electrophile. Naturally the two species react. The enolate attacks the carbonyl carbon of the aldehyde, creating a new carbon–carbon bond and giving the halohydrin intermediate. The new bond forms between the α-carbon of the enolate and the carbonyl carbon of the aldehyde.

In the next step the halohydrin closes into an epoxide. The oxygen of the newly formed alkoxide acts as a nucleophile and performs an intramolecular SN2 reaction on the same α-carbon that originally carried the chlorine. This displaces chloride and forms the three-membered epoxide ring.

At this point some students notice that the α-carbon looks tertiary and ask how an SN2 process is even possible. Under normal conditions a tertiary carbon is far too crowded for SN2 attack. The key difference here is that we are forming a three-membered ring. When we look at the transition state from the Newman projection, with the oxygen on the front carbon and the carbon bearing chlorine as the back carbon, we can arrange the groups so that the oxygen and the chlorine are anti-periplanar. In that orientation the oxygen lone pair can overlap directly with the σ* orbital of the C–Cl bond. Because of that alignment, there is no meaningful steric hindrance and the reaction proceeds very easily. Three-membered ring closure behaves differently from standard SN2 chemistry, so the usual steric limits do not apply here.

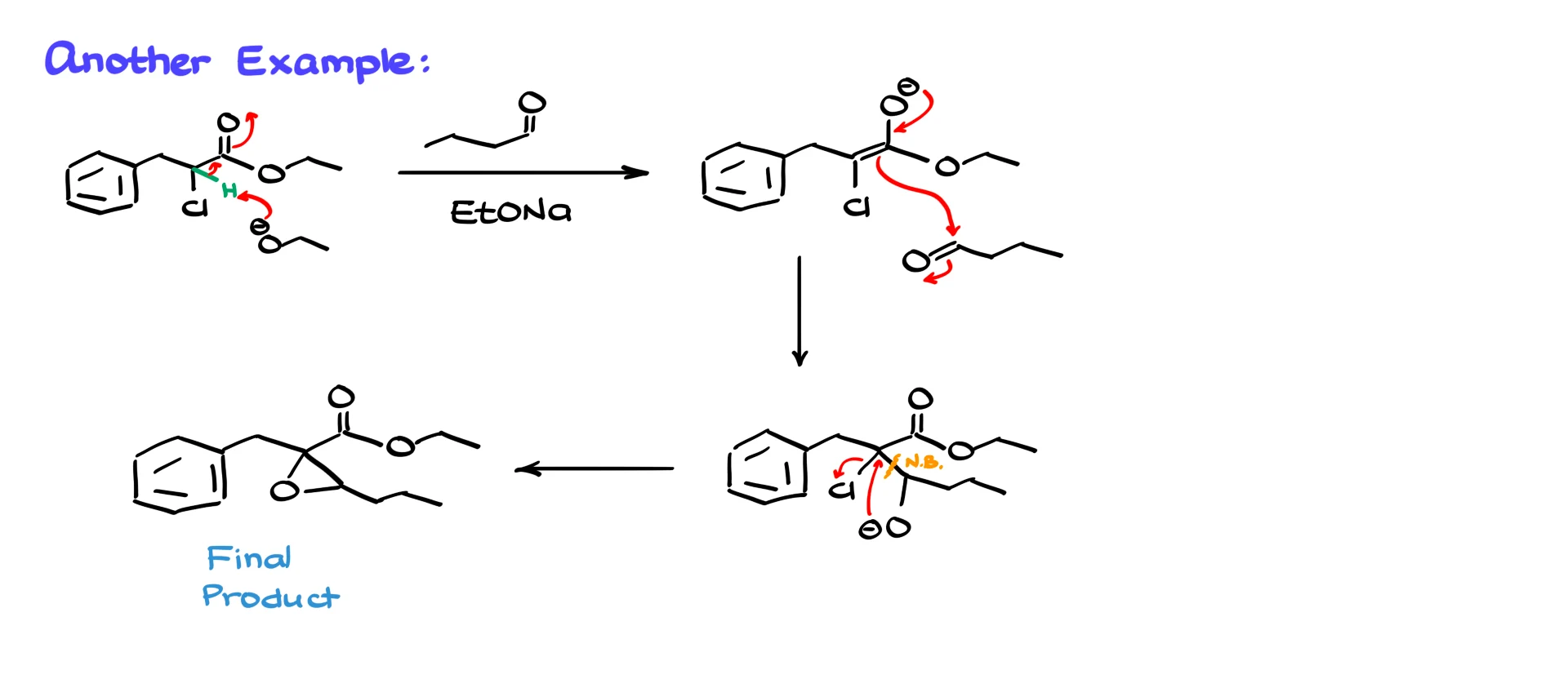

Another Example

The second example follows exactly the same pattern.

We deprotonate the α-carbon with base to give the enolate, react the enolate with an aldehyde to form the halohydrin, and then close the ring. Once again the oxygen performs an intramolecular SN2 attack on the α-carbon, chloride leaves, and we obtain the epoxide.

It is a remarkably elegant reaction and one of my favorites for building epoxides directly from simple carbonyl compounds.