Imine and Enamine Hydrolysis

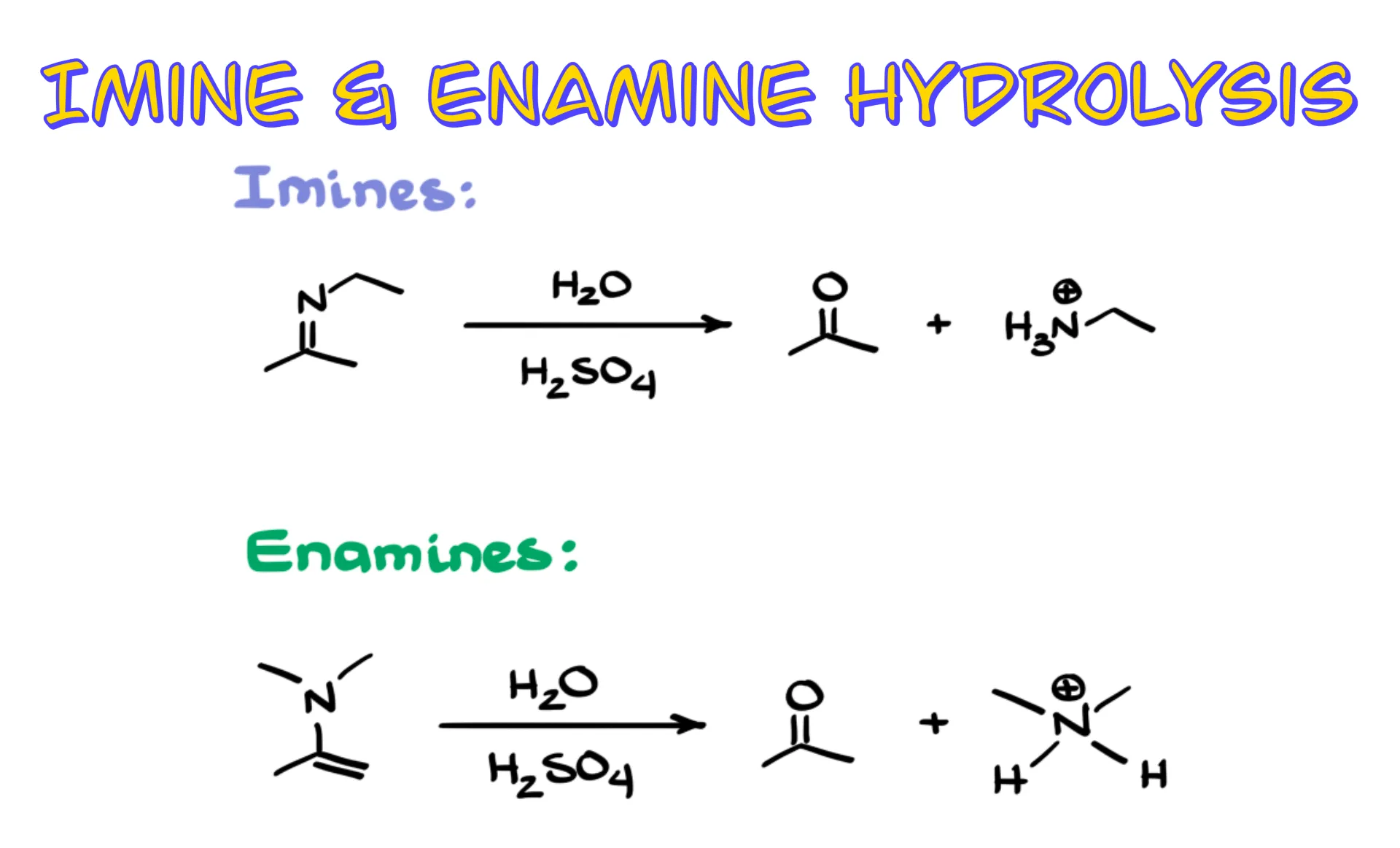

In this tutorial we will look at the hydrolysis of imines and enamines. If you watched the tutorial on imine and enamine formation, this is the same story in reverse.

We start with an imine or an enamine and use acidic water to turn them back into the corresponding carbonyl compounds and amines.

To keep things simple I will use H₃O⁺ as a generic way to show an acidic aqueous solution. In an actual reaction you might see water with sulfuric acid, water with p-toluenesulfonic acid, or water with HCl. It makes no difference mechanistically because they all produce H₃O⁺.

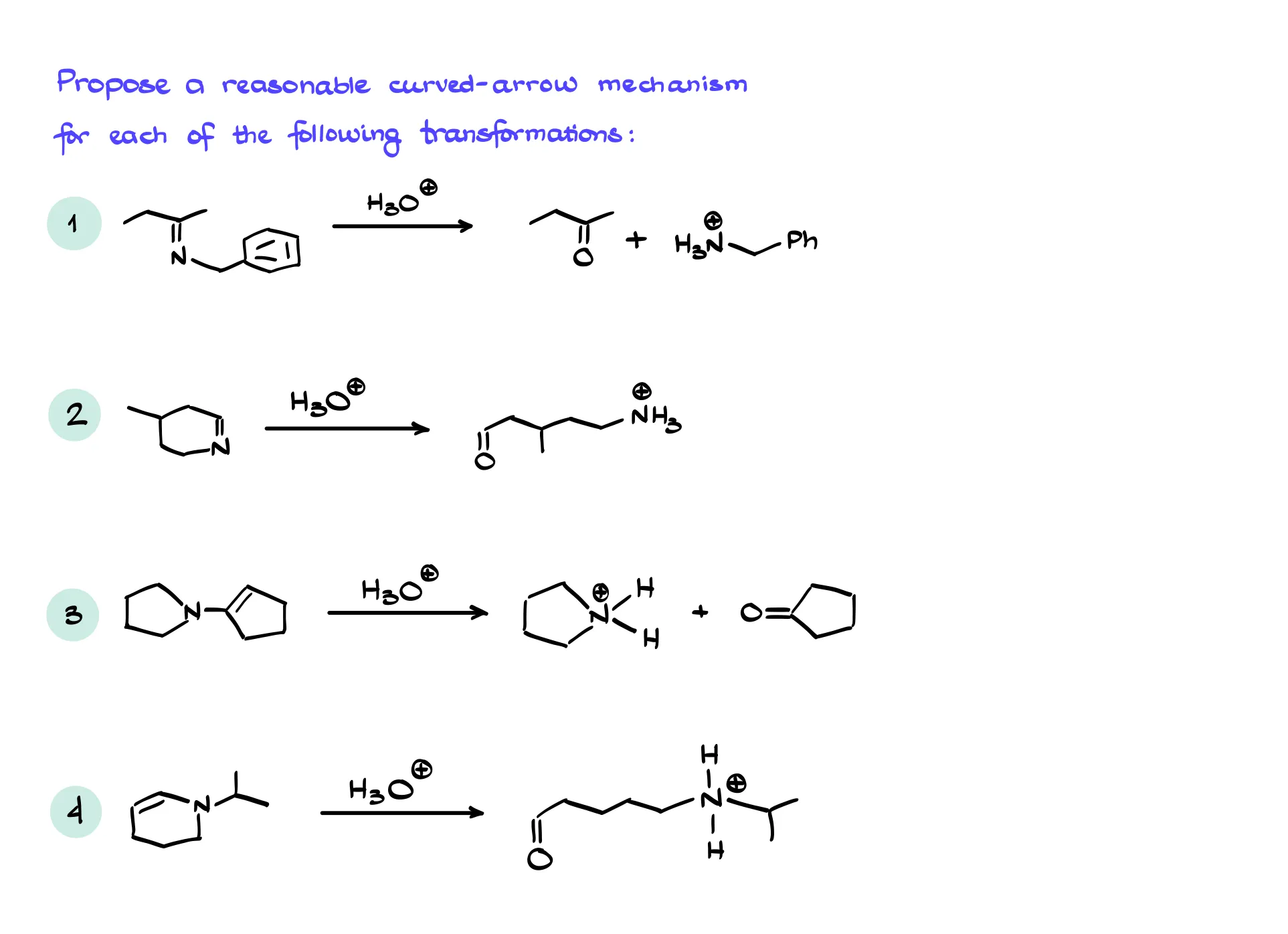

Imine Hydrolysis

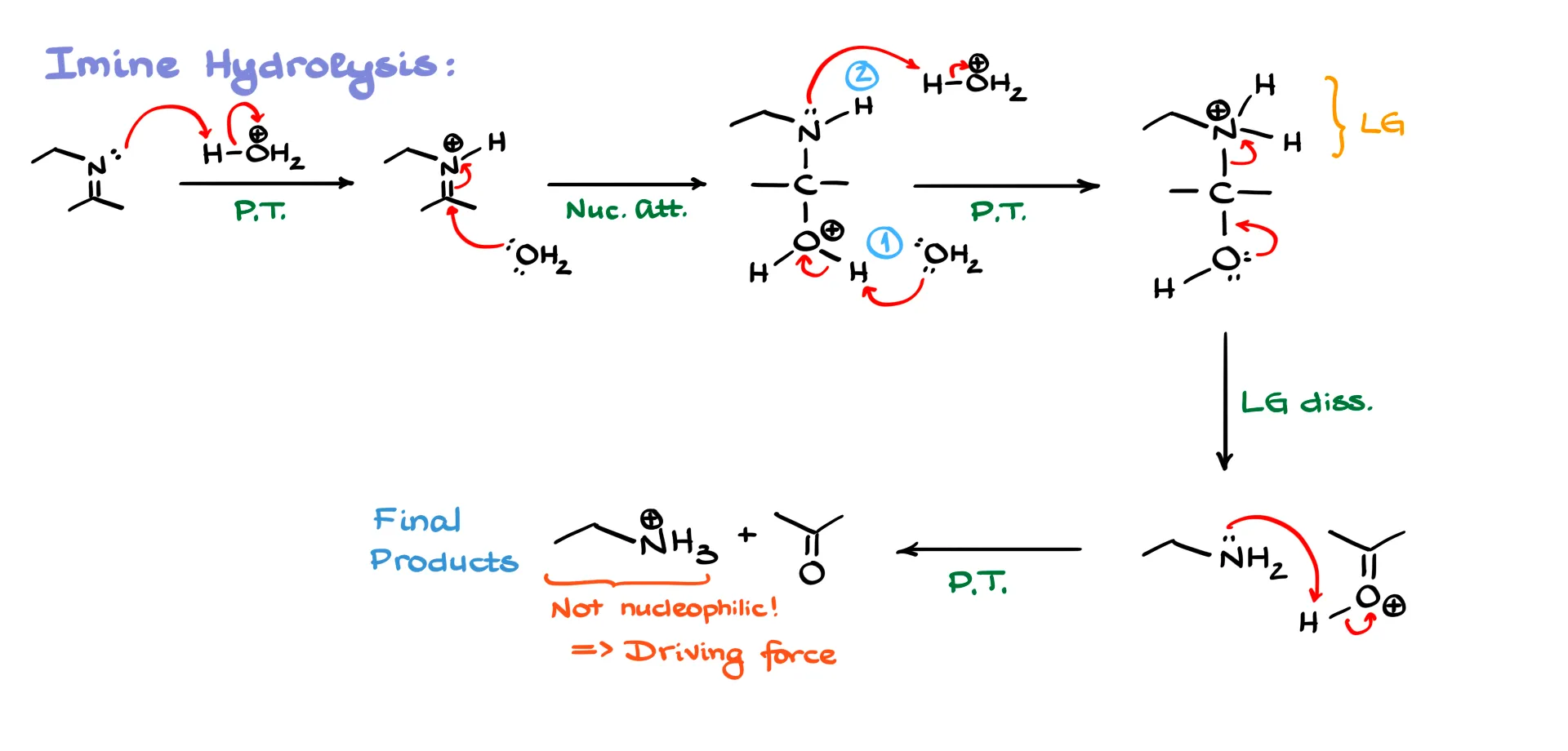

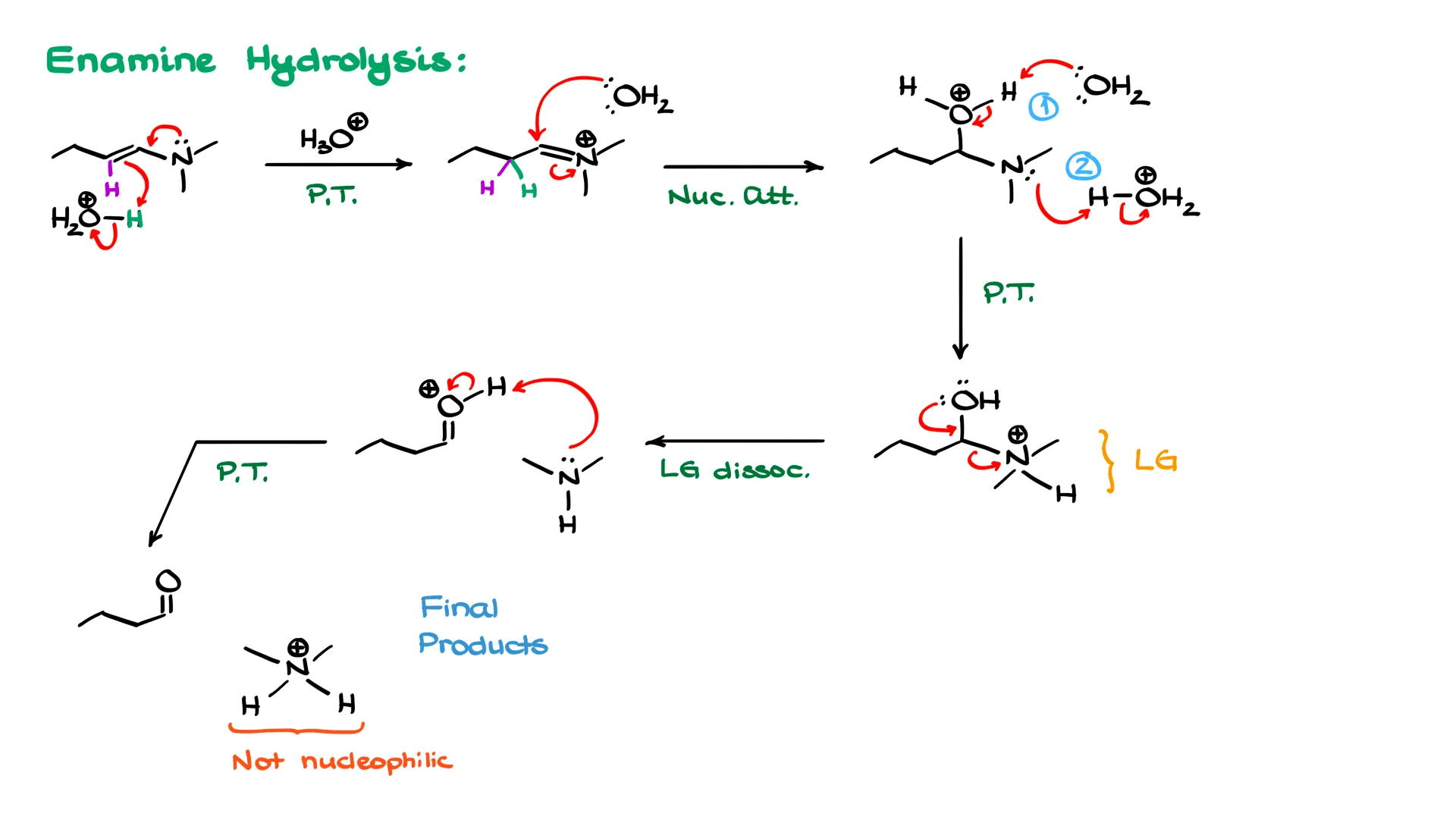

For the first mechanism, imine hydrolysis, I’ll redraw H₃O⁺ as H–H₂O⁺ so I can show the first proton transfer clearly. The imine grabs a proton from H₃O⁺ and forms a protonated iminium ion. That species is strongly electrophilic, so the only nucleophile in solution that can attack it is water. Water attacks the iminium carbon and gives a tetrahedral intermediate with a positively charged oxygen.

At this point we need a proton transfer. It is tempting to draw it as an intramolecular event, but that would force a tiny four-membered transition state, which is unlikely. Instead we let water act as a base to pull a proton off the oxygen, and an oxonium ion in solution protonates the nitrogen. If you were drawing this step by step you would usually deprotonate first and protonate the nitrogen second. After these transfers we have a protonated nitrogen next to the oxygen. That protonated nitrogen now behaves as a leaving group. The oxygen helps push it out, and we form a free amine along with a protonated carbonyl.

Because an amine is basic and the carbonyl oxygen is protonated, the two immediately undergo an acid–base reaction. The amine takes the proton and we end up with the neutral carbonyl and the protonated amine. Since the amine is protonated, it is no longer nucleophilic, so the reverse reaction cannot happen. This final proton transfer is the driving force for the entire process. Up until that point almost everything is reversible, but once the amine becomes R-NH₃⁺, the equilibrium is effectively one-way.

If you compare these steps to the imine formation mechanism, you will see that we are walking through the same intermediates but in the opposite direction. If you fully understand one mechanism, you can reconstruct the other without memorization.

Imine Hydrolysis Shortcut

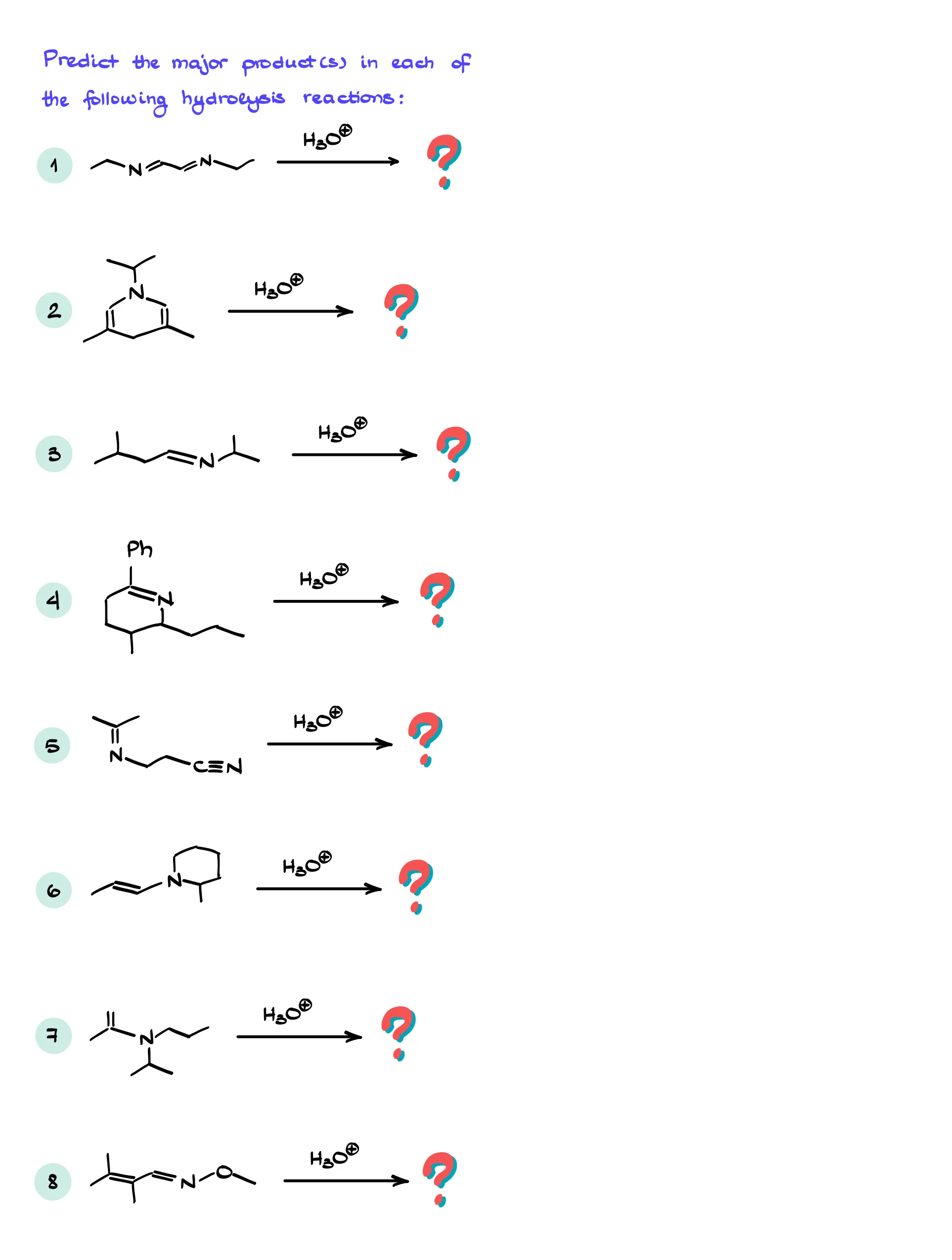

There is also a fast shortcut for predicting the hydrolysis products.

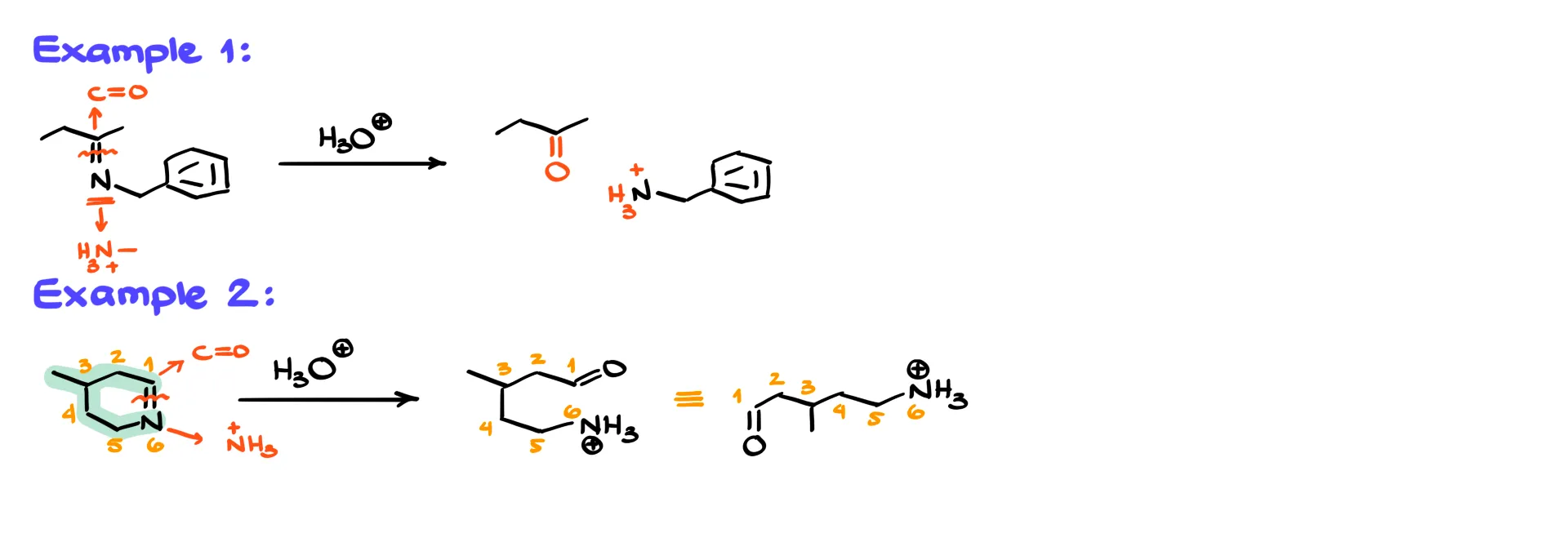

Because hydrolysis breaks the C=N bond, the nitrogen becomes NH₂ (or NH₃⁺ under acidic conditions) and the carbon attached to that nitrogen becomes a carbonyl. So for a given imine, sketch the chain up to the nitrogen, change the nitrogen into NH₂, then convert the carbon it was attached to into a carbonyl. Since we are in acidic solution, we usually show the nitrogen as NH₃⁺ instead of NH₂.

For example, in the first reaction we identify the C=N bond in an imine. The nitrogen becomes NH₃⁺ and the carbon becomes a carbonyl. If the rest of the molecule is a simple chain, we draw the carbonyl-containing fragment on one side and the protonated amine on the other. In a cyclic example we still break only the C=N bond. The ring stays intact everywhere else, so instead of forming two separate products we end up with a single open-chain product that contains both functional groups.

Enamine Hydrolysis

Now let’s move to enamine hydrolysis.

An enamine has a nitrogen sitting next to a carbon–carbon double bond. Instead of protonating the nitrogen first, we protonate the double bond. The curved arrows begin at the nitrogen, the π bond grabs the proton from H₃O⁺. That proton adds to one of the carbons of the double bond. The carbon already had a hydrogen, and now it has the new proton as well, so it looks like the double bond has shifted, but in reality we have added a proton.

This gives an iminium ion, and from here the mechanism mirrors the imine hydrolysis mechanism. Water attacks the iminium carbon, giving an intermediate with a protonated oxygen and a neutral nitrogen. As before, instead of an intramolecular proton transfer, water deprotonates the oxygen and H₃O⁺ protonates the nitrogen. Once nitrogen is protonated, it can leave with the help of the oxygen, producing a free amine and a protonated carbonyl. The amine then pulls off that proton, giving the final carbonyl and the protonated amine. Again, protonation of the amine is the driving force that prevents reversal.

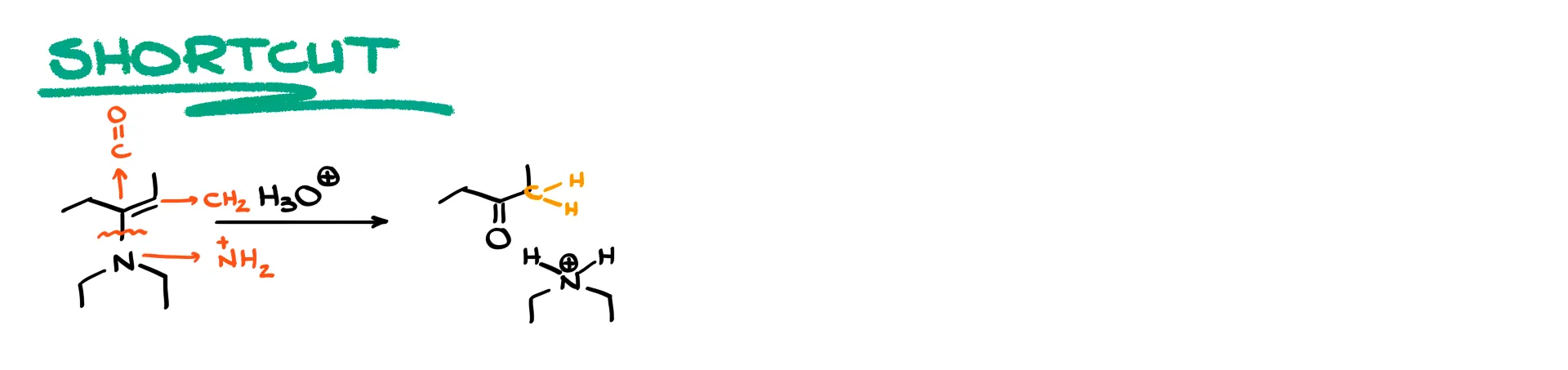

Enamine Hydrolysis Shortcut

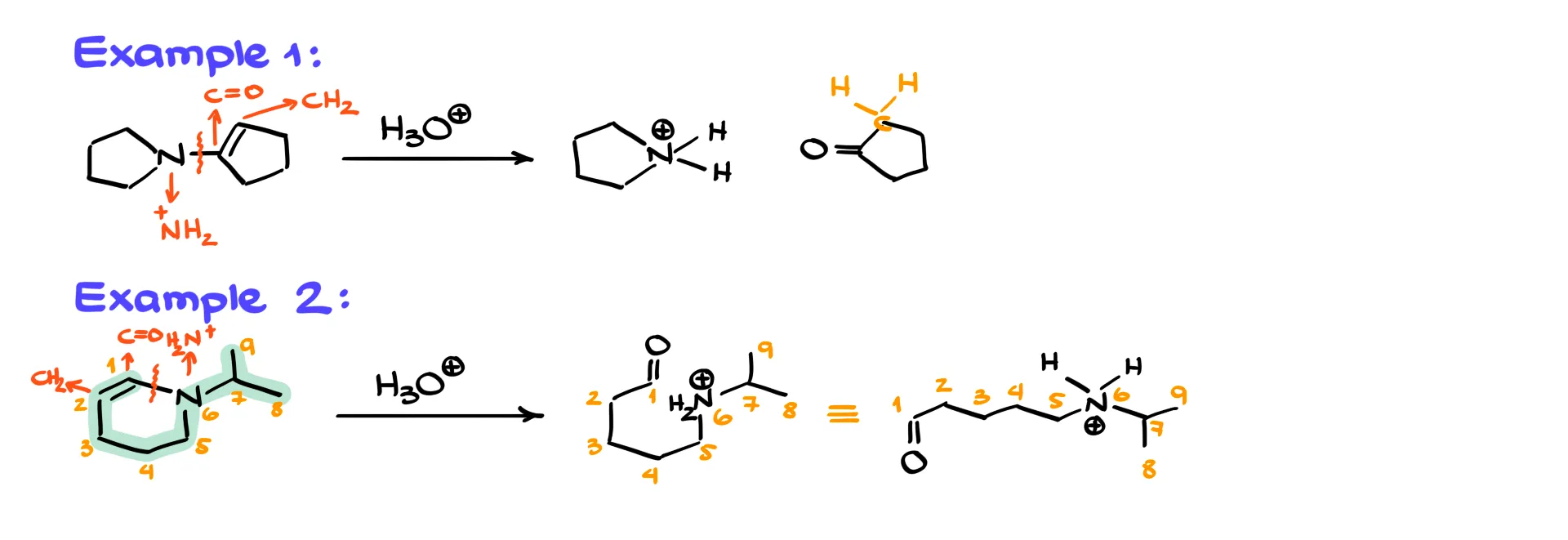

The shortcut for enamine hydrolysis works like the imine shortcut but with one added detail. We break the C–N single bond that sits next to the C=C bond. The nitrogen becomes NH₂ (or NH₃⁺). The carbon connected to the nitrogen becomes a carbonyl. The other carbon of the original double bond becomes CH₂ because the double bond is not preserved. So when drawing the products, show the carbonyl at the carbon originally bonded to nitrogen, convert the partner carbon of the double bond into a CH₂ group, then draw the nitrogen fragment as NH₃⁺ with its substituents.

In a cyclic example we again break only the C–N bond. The rest of the ring stays intact, so we obtain one extended molecule. If we number the atoms in the starting material and check them after drawing the product, everything lines up correctly and nothing is lost.

Hydrolysis of imines and enamines follows predictable patterns, and once you see the logic it becomes straightforward. Take time to practice these mechanisms and shortcuts because they appear on exams all the time. As always, if you have questions or comments, leave them below!

Practice Questions

Answers

Would you like to see the answers and check your work?

Sign up or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!