Carbodiimide-Mediated Coupling

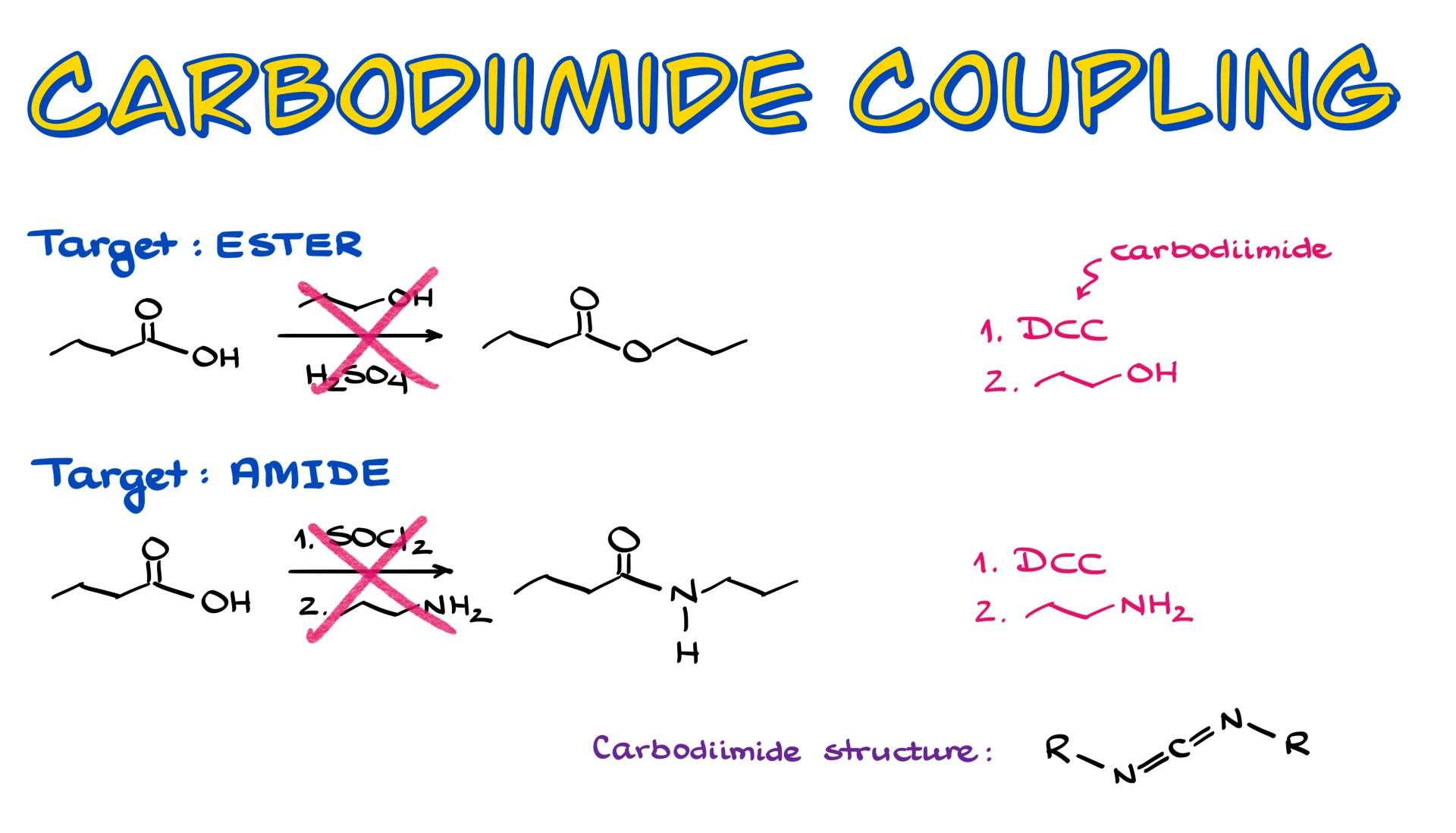

In this tutorial I want to talk about carbodiimide coupling, a very useful method for converting carboxylic acids into esters or amides when classic Fischer esterification or acid chlorides are not good options. This approach lets us avoid harsh reagents, strong acids, and high temperatures, which is why it shows up so often in modern synthesis.

Before we look at the mechanism, let’s talk about what carbodiimides actually are. A carbodiimide is a functional group where a central carbon is double-bonded to two nitrogens. Each nitrogen has an R group attached to it. The exact identity of those R groups mostly affects physical properties like solubility and whether the reagent is a solid or a liquid. Chemically, all carbodiimides behave in essentially the same way, and that central N=C=N unit is the reactive part.

Mechanism of Carbodiimide Coupling

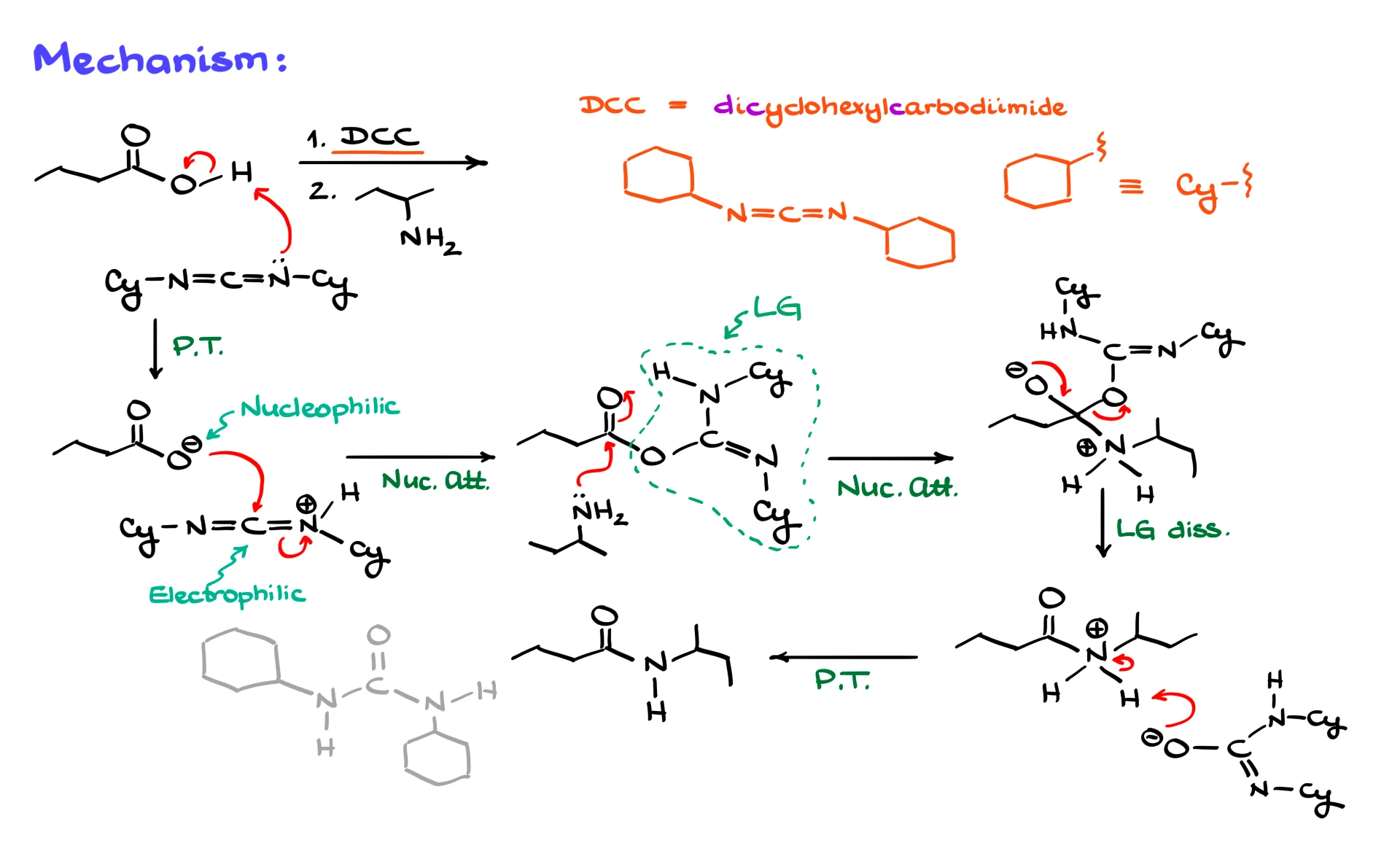

Now let’s walk through the mechanism using a concrete example. Suppose we want to couple butanoic acid with sec-butylamine to form an amide, and we choose DCC as our coupling reagent. DCC stands for dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. Structurally, it has the carbodiimide group in the middle and two cyclohexyl groups on the sides. To save time, those cyclohexyl groups are often abbreviated as “Cy,” and I will do the same here.

The first step is a proton transfer. The carboxylic acid protonates one of the nitrogens of DCC. As a result, we form a carboxylate anion and a protonated carbodiimide. This sets up the key interaction. The carboxylate is nucleophilic, and the protonated carbodiimide is electrophilic, so they react immediately.

The oxygen of the carboxylate attacks the central carbon of the carbodiimide. The electrons shift onto nitrogen, giving a rather ugly-looking intermediate, but this is the whole point of the reaction. We have effectively transformed the OH group of the carboxylic acid into an excellent leaving group. That carbodiimide-derived fragment attached to oxygen is now a very good leaving group, far better than OH itself.

Once the carboxylic acid is activated, we bring in our nucleophile, in this case an amine. The nitrogen of the amine attacks the carbonyl carbon of the activated carboxylic acid, forming a tetrahedral intermediate. From there, the leaving group departs, and we form the amide bond. A final proton transfer gives us the neutral amide and the spent carbodiimide byproduct. That byproduct rapidly tautomerizes into a more stable urea-type structure, but from a synthetic perspective it is just waste.

Depending on how you draw the mechanism, you might show deprotonation of the amine first and then loss of the leaving group, or loss of the leaving group first followed by deprotonation. Either sequence is fine. You end up with the same final products, and textbooks differ in how they present those last steps.

So the big picture here is simple. Carbodiimide coupling works by activating the OH group of a carboxylic acid, turning it into a good leaving group, and then letting a nucleophile such as an amine or an alcohol attack to form an amide or ester. The reaction runs under mild conditions and often works even in aqueous media, depending on the carbodiimide used. That makes it an excellent alternative to acid chlorides or strong acid-catalyzed esterifications.

Common Carbodiimides

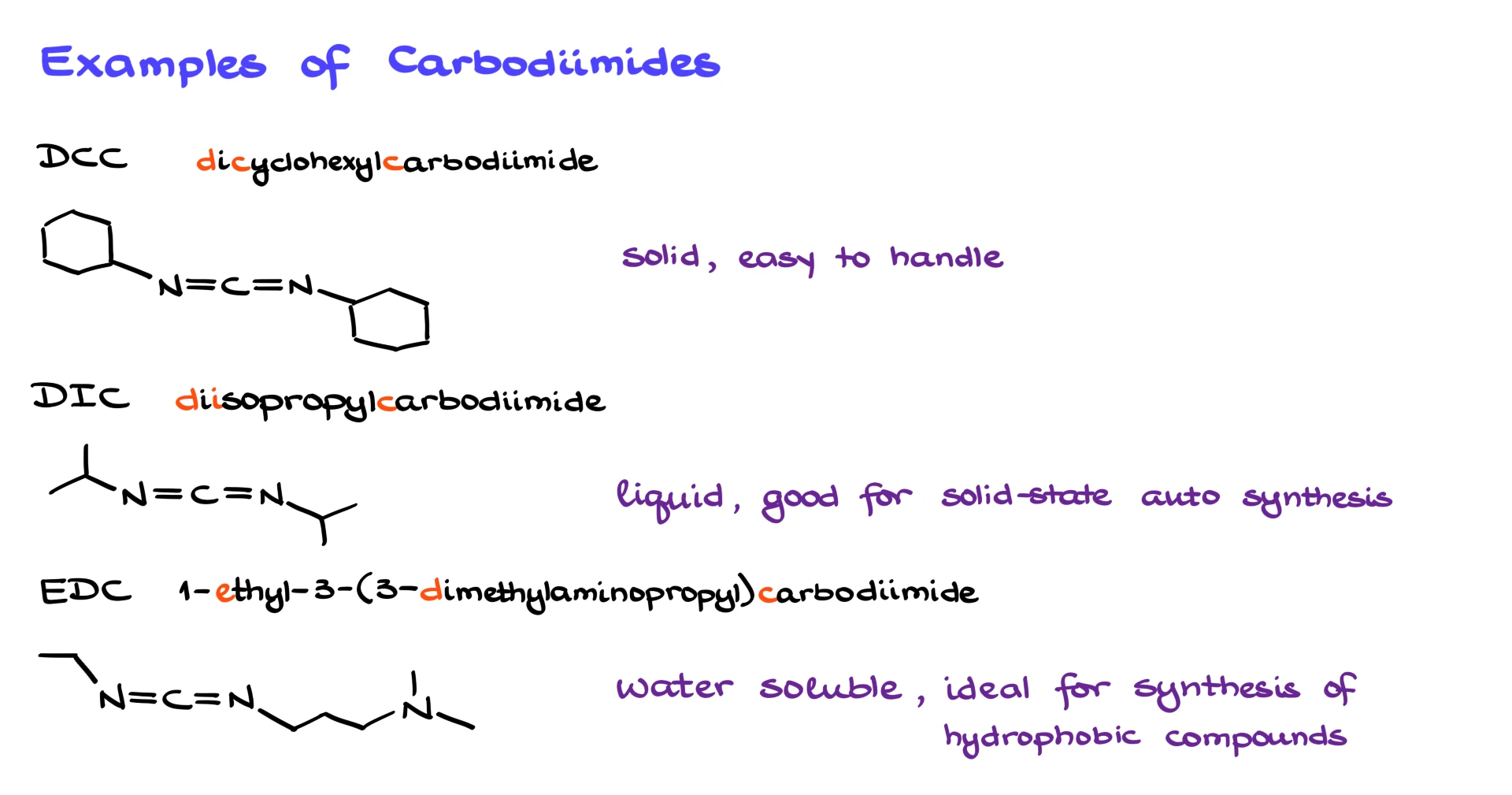

Now let’s talk briefly about common carbodiimides.

We have already seen DCC, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. It is a solid and one of the earliest coupling reagents developed. It is easy to handle but not always ideal. Another popular option is DIC, diisopropylcarbodiimide. This one is a liquid, which makes it very convenient for solid-phase synthesis because it is easy to wash away excess reagent. A third very common reagent is EDC, which stands for 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide. EDC is water soluble, which makes it perfect for reactions involving polar, water-soluble starting materials.

Carbodiimide COupling Reaction Examples

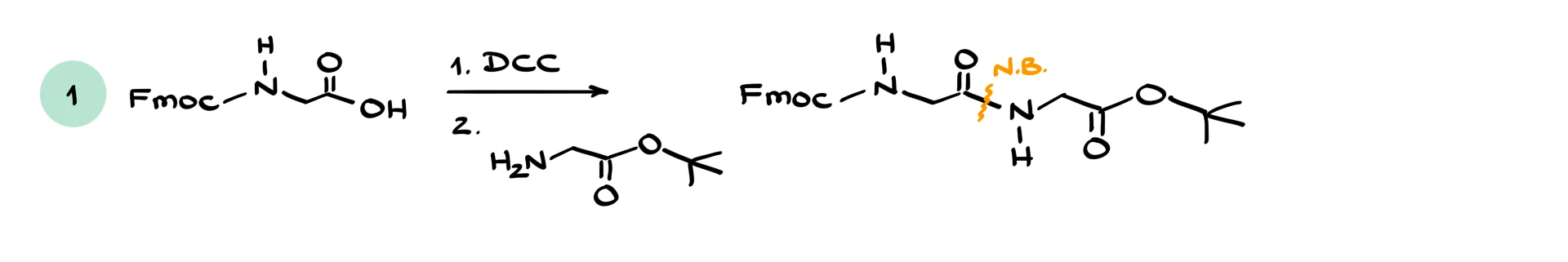

Let’s look at a few examples.

In the first case, we have glycine protected on the nitrogen with an Fmoc group. That part of the molecule is inert for our purposes. The carboxylic acid reacts with an amine from another glycine derivative whose carboxyl group is protected. Using DCC, we form a new bond between the carbonyl carbon of the acid and the nitrogen of the amine, giving a dipeptide. The key transformation is formation of the C–N bond and loss of the OH group.

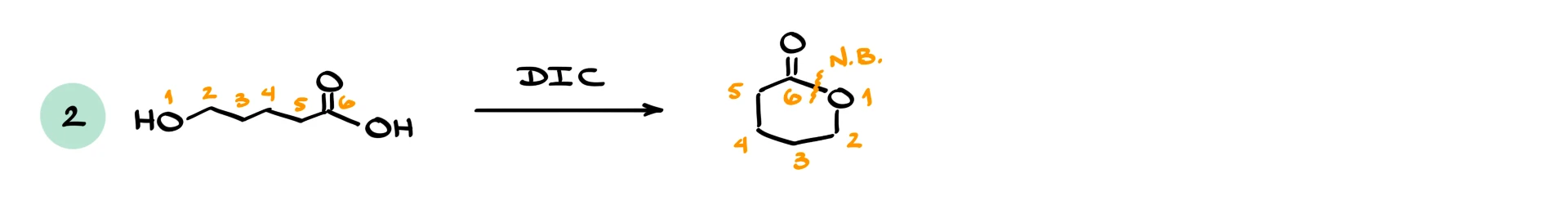

In the second example, we have an intramolecular reaction. The molecule contains both a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Carbodiimide activation converts the acid into an electrophile, and the internal OH group attacks. Counting the atoms shows that we form a six-membered ring, giving a lactone. The new bond forms between the oxygen of the alcohol and the carbonyl carbon of the original carboxylic acid.

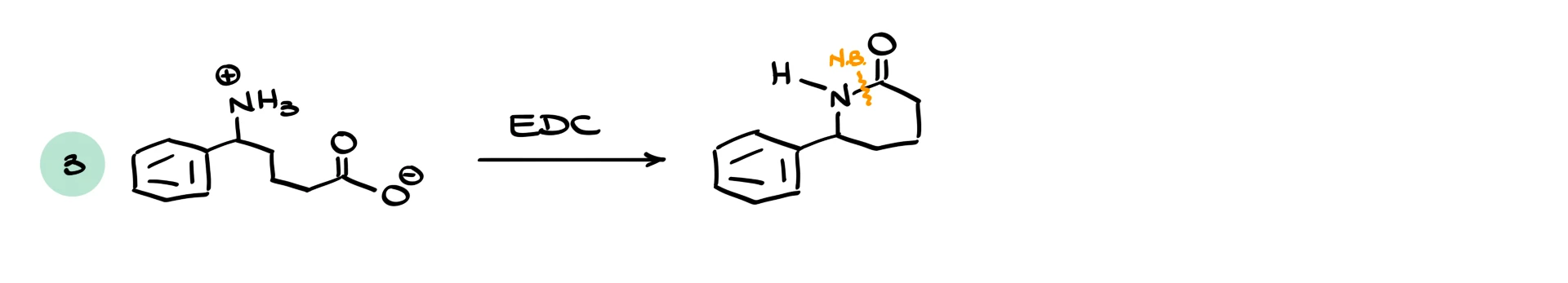

In the third example, we have a zwitterionic molecule with a carboxylate and a protonated amine. We use EDC as the coupling reagent. Both the starting material and EDC are water soluble, so the reaction can be run in aqueous solution. The amine attacks the activated carboxyl group, forming an amide. The final product is much less polar than the starting materials, so it often precipitates out of water, making purification very easy.

From a mechanistic standpoint, all of these reactions work in exactly the same way regardless of whether you use DCC, DIC, or EDC. The differences are practical, not chemical. Some reagents are solids, some are liquids, some are water soluble, and you choose based on what makes your synthesis cleaner and easier.

Even though I did not explicitly draw every mechanism for these examples, you should practice them yourself. Being comfortable with the carbodiimide coupling mechanism is important because it can show up on exams, and if you understand the logic, it is very straightforward.

Mechanisms for the Reactions Above

Would you like to see the answers and check your work?

Sign up or login if you’re already a member and unlock all members-only content!