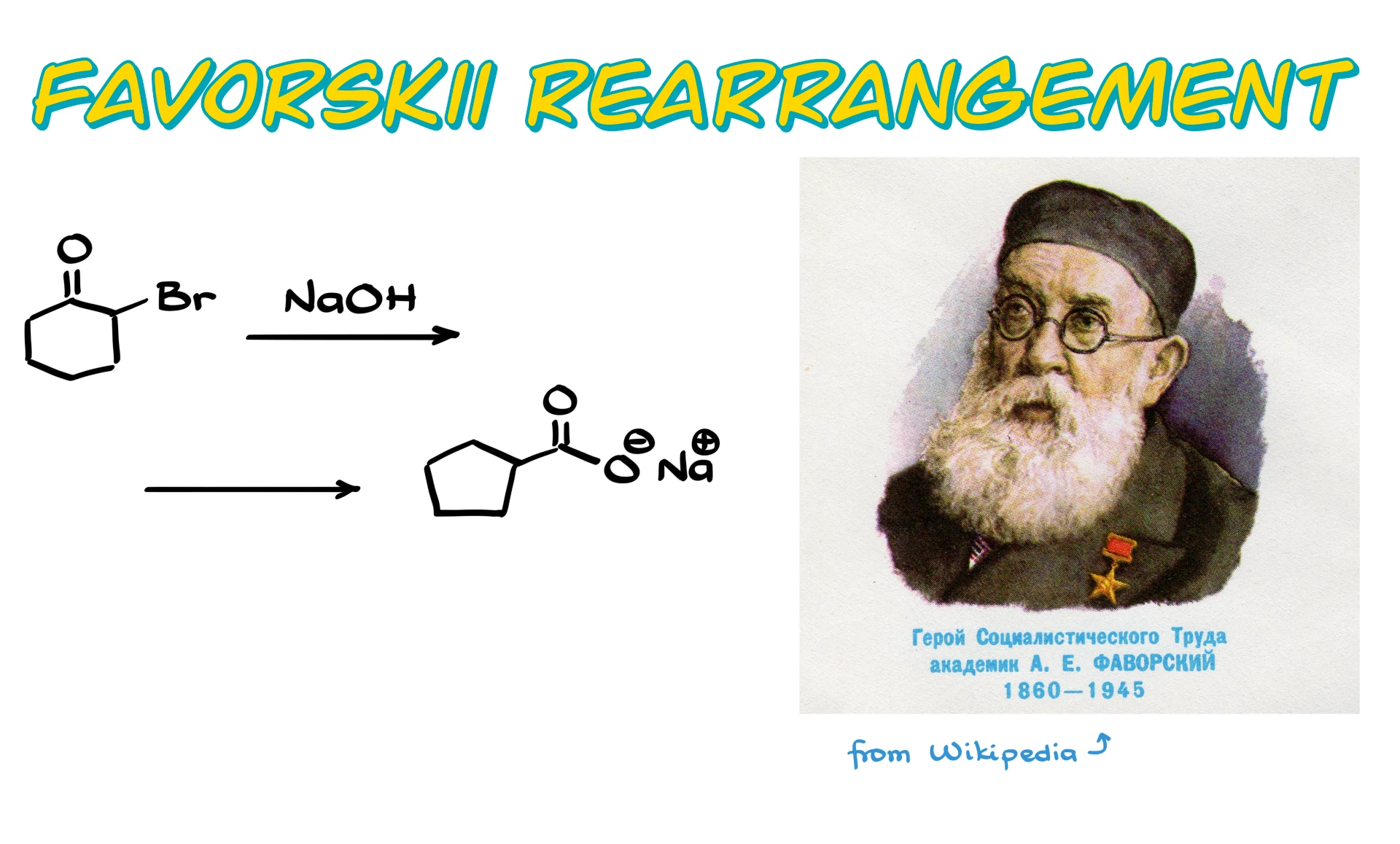

Favorskii Rearrangement

In this tutorial I want to talk about the Favorskii rearrangement, which is honestly one of my favorite reactions in all of organic chemistry.

Favorskii Rearrangement Mechanism

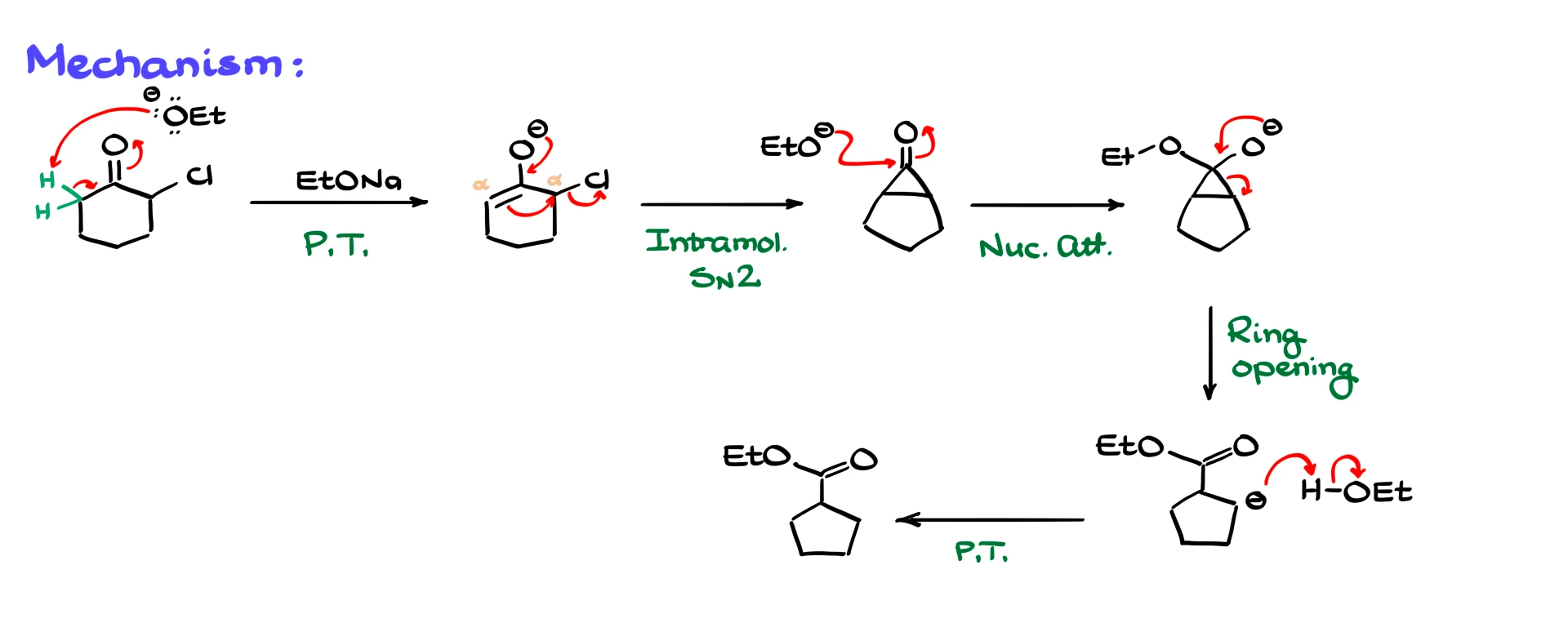

So how does this reaction actually work? There are two classic mechanistic version, and we will start with the most common one.

We typically begin with an α-halogenated carbonyl. In the first example I have α-chlorocyclohexanone, and the reaction is carried out under basic conditions. That means the first step is an enolization at one of the α-positions. I have already marked the α-hydrogens I care about. The base, ethoxide, comes in and removes one of those α-protons, giving the corresponding enolate.

You might be wondering why we do not pull off the proton next to the chlorine. That hydrogen is more acidic, and yes, enolization at that position can happen in reality, but it does not lead us anywhere productive, so mechanistically it is a dead end. That is why we usually ignore it when we draw this reaction.

From the enolate the next step is an intramolecular substitution. The enolate acts as a nucleophile and performs an intramolecular SN2 reaction on the carbon bearing the chlorine, displacing chloride. This connects the two α-carbons and forms a three-membered ring. The result is a cyclopropanone intermediate connected to what is now a five-membered ring. In other words, the original six-membered ring has contracted by one carbon.

Cyclopropanones are extremely strained and very reactive toward nucleophiles. Since we are in basic solution with ethoxide present, ethoxide is a perfect nucleophile. It attacks the carbonyl carbon of the cyclopropanone, giving a tetrahedral intermediate. That intermediate collapses as the three-membered ring opens. The electrons from the C–C bond move, breaking the ring and generating a carbanion. This carbanion is not particularly stable and is also a very strong base. It immediately grabs a proton from the solvent, which is usually the corresponding alcohol, to give the final product. In this example the product is an ester, and the ring has contracted from six members to five.

So to recap this classic Favorskii mechanism, we start with a proton transfer to form the enolate, then an intramolecular SN2 reaction to form the cyclopropanone, followed by nucleophilic attack to give a tetrahedral intermediate, then three-membered ring opening, and finally a proton transfer that gives the rearranged product. Depending on the nature of the nucleophile and the reaction conditions, the product can be an ester, an amide or a carboxylic acid.

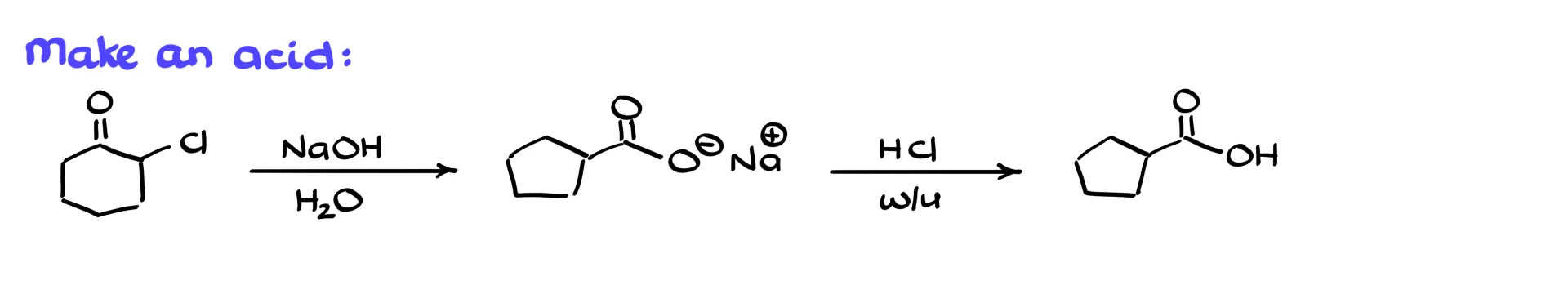

For example, if I want a carboxylic acid instead of an ester, I can start from the same α-chlorocyclohexanone but use aqueous sodium hydroxide instead of sodium ethoxide. That gives the carboxylate under basic conditions, and after an acidic workup I obtain the corresponding carboxylic acid.

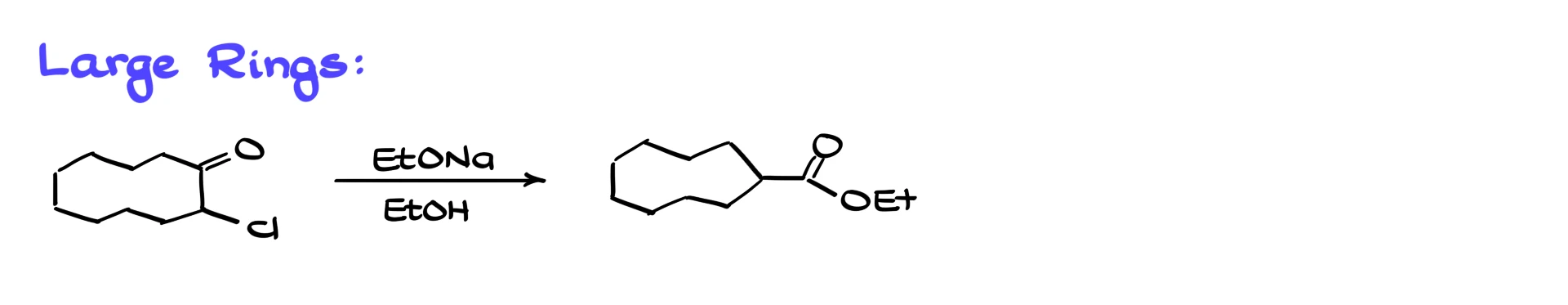

Large Rings vs Small Rings

The Favorskii rearrangement is particularly useful for ring contractions, especially when we are dealing with six-membered or larger rings. For instance, if I start with a ten-membered α-halogenated ring and subject it to Favorskii conditions, I obtain the corresponding nine-membered ring.

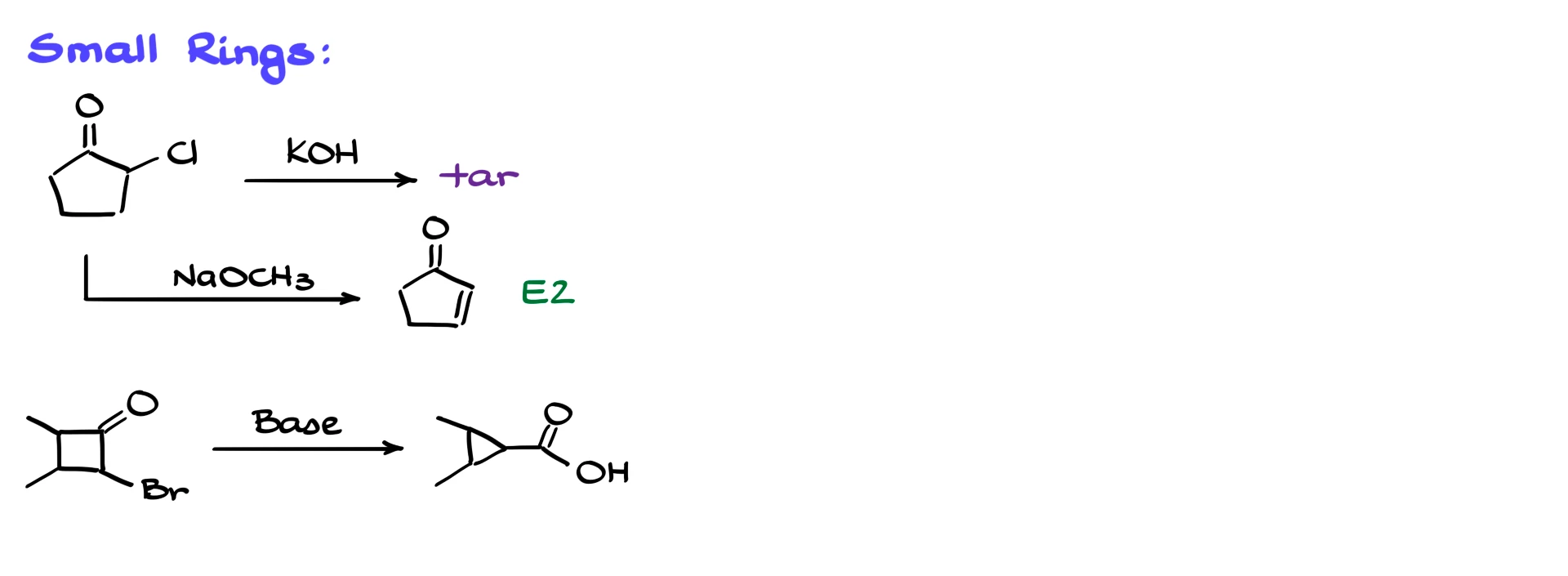

Things get more interesting when we move to smaller rings.

If I try the same strategy on a five-membered ring, instead of a nice product I mostly get tar, which usually ends up in the waste along with the flask. You might think this is just a matter of changing the base. For example, what happens if instead of sodium hydroxide I use sodium ethoxide? In that case the main outcome is not a rearranged product but an elimination product. We get an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound rather than a contracted ring.

Quasi-Favorskii Mechanism

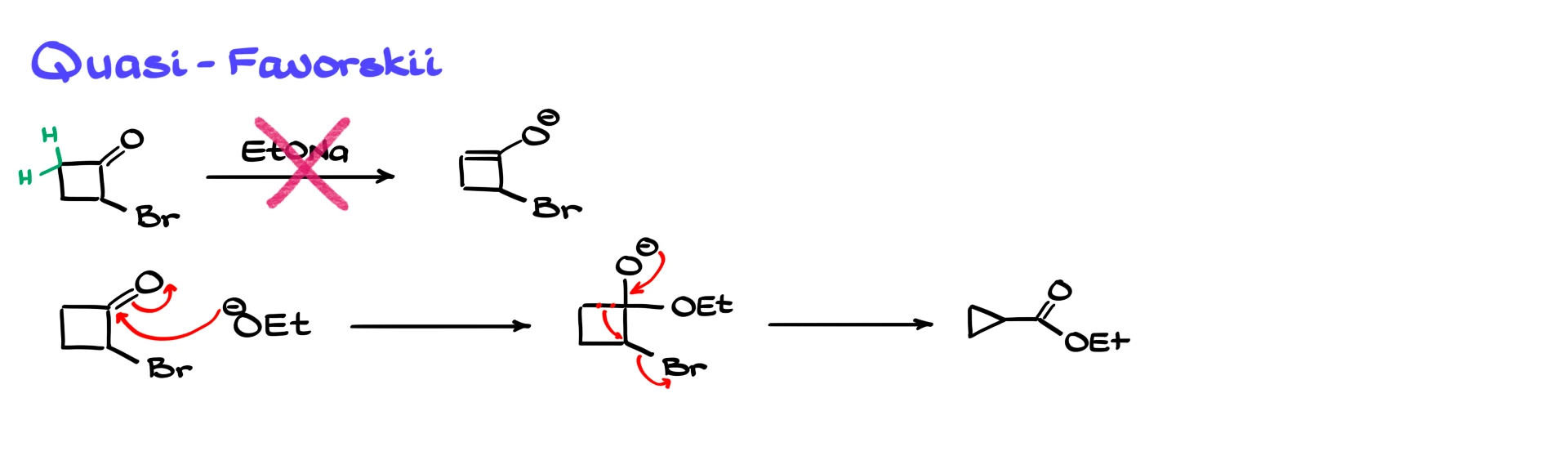

So if a five-membered ring does not work, surely a four-membered ring should be even worse, right? Surprisingly, that is not true. The rearrangement can work for four-membered rings, but through a different mechanistic pathway. This variation is sometimes called a quasi-Favorskii mechanism or a benzylic-type mechanism because it resembles the chemistry of the benzilic rearrangement.

For a strained four-membered ring we do not go through a classic enolate first. If you try to imagine forming the enolate directly on a four-membered ring, you end up with an incredibly strained system. The enolate would be so unstable that enolization is essentially disfavored. Instead, the key step is a direct nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl. Carbonyls on very small rings, such as three- or four-membered rings, are highly electrophilic due to ring strain. The base or alkoxide attacks the carbonyl carbon, giving a tetrahedral intermediate. From there, the oxygen collapses back down to reform the carbonyl, and the adjacent C–C bond breaks, expelling the halide as a leaving group. In this way the ring contracts, and we obtain the product directly as an ester, carboxylic acid or related derivative, without ever forming a free carbanion intermediate. The mechanism is different, which is why the reaction can succeed in cases where a classic Favorskii pathway would fail.

Here’s an example from Ross’ paper where they did a contraction of a 4-membered ring into a 3-membered ring.

Acyclic Favorskii Rearrangement

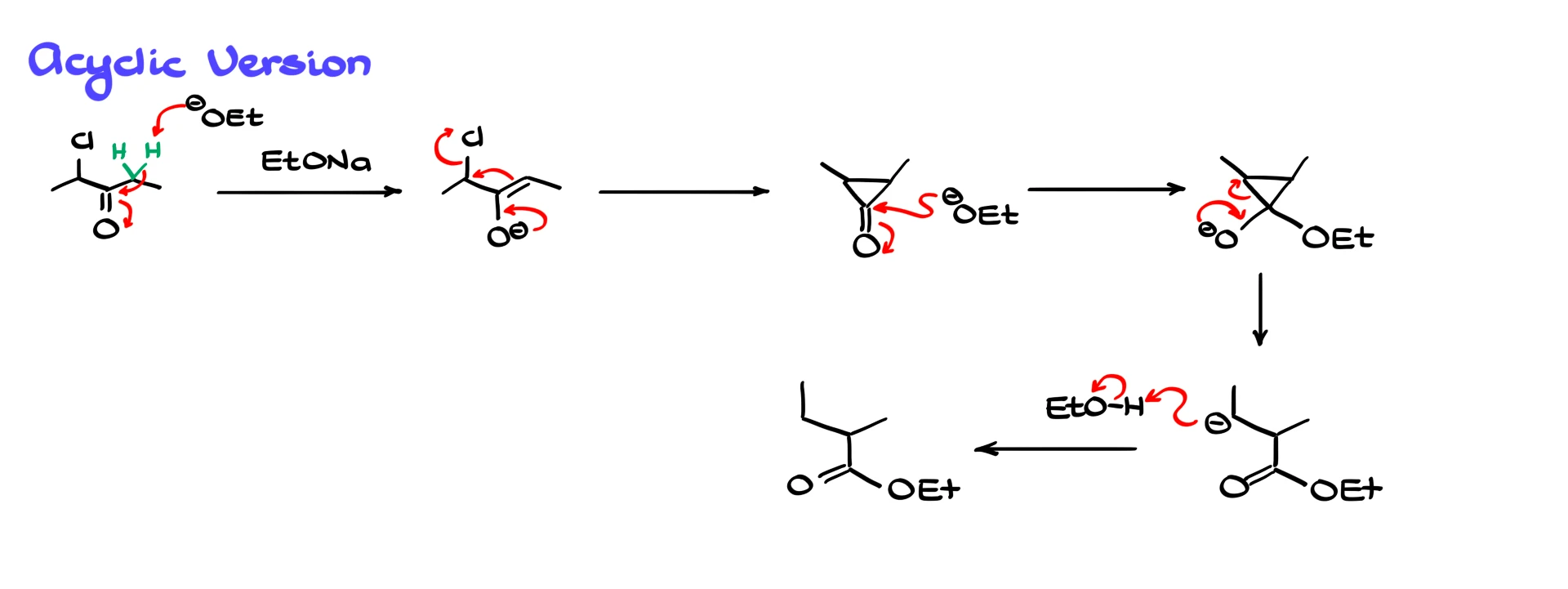

The Favorskii rearrangement also works for open-chain systems.

For example, take a chlorinated pentanone with the chlorine at the α-position. Under basic conditions with sodium ethoxide, the base removes an α-proton to form an enolate. The enolate then performs an intramolecular attack to generate a cyclopropanone intermediate attached to the rest of the chain. Ethoxide attacks the cyclopropanone carbonyl, the three-membered ring opens, and a carbanion forms. As before, this carbanion immediately takes a proton from the solvent, giving an ester as the final product.

Regiochemistry of the Favorskii Rearrangement

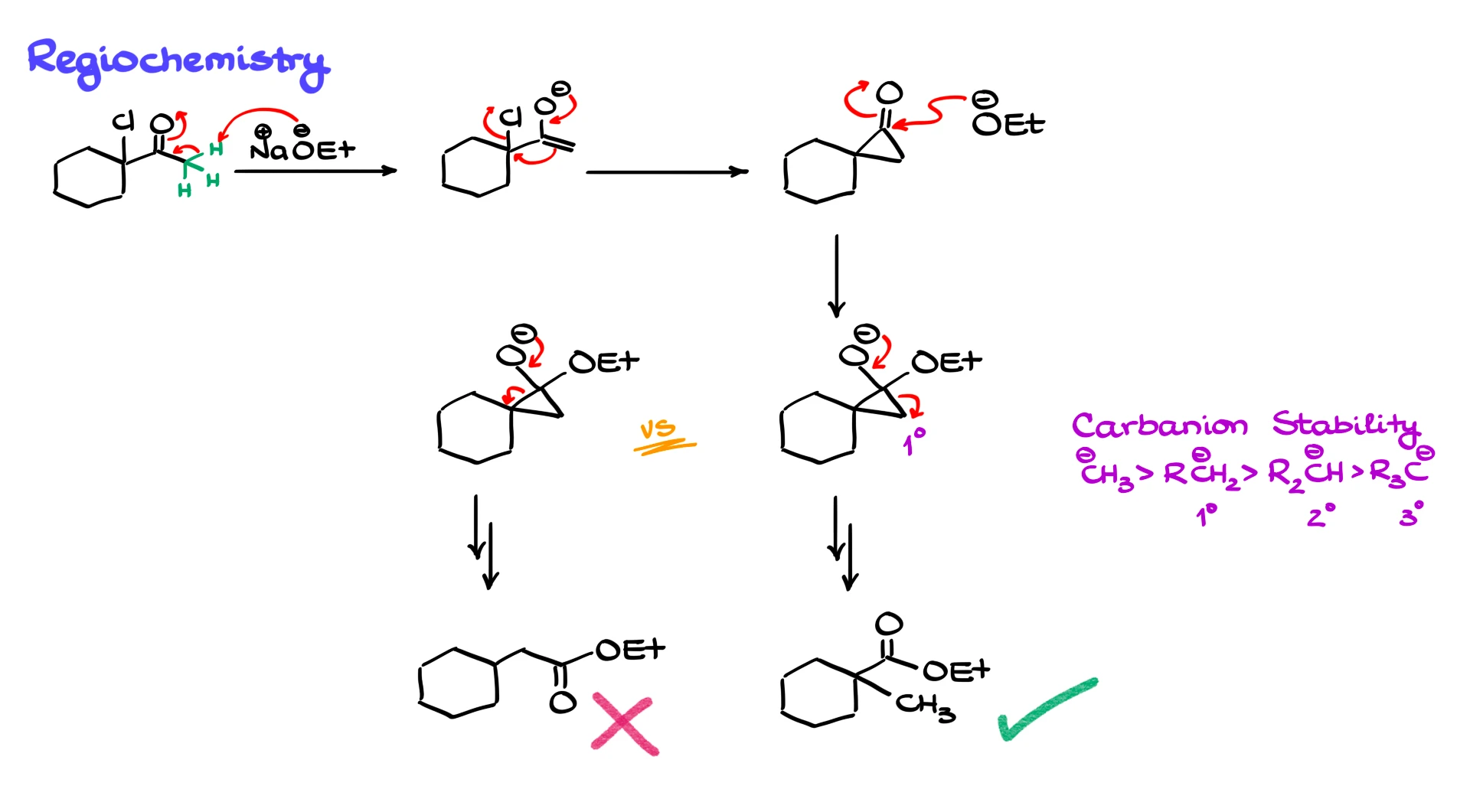

Now let us talk about regiochemistry. Up to this point the examples have been symmetrical or effectively symmetrical, so it did not matter how the ring opened. But what happens when the starting material is not symmetrical?

Suppose we have an unsymmetrical α-chloro ketone and we treat it with sodium ethoxide in ethanol. As before, the ethoxide removes an α-proton and forms an enolate. The enolate then undergoes intramolecular SN2 to give an unsymmetrical cyclopropanone intermediate. The ethoxide then attacks the carbonyl to form a tetrahedral intermediate. At that stage, when the three-membered ring opens, we have two possible pathways. The ring can open by breaking the bond on the right side, leading after proton transfer to one ester, or it can open on the left side, leading after proton transfer to a different ester.

Both pathways are mechanistically possible, but experimentally we observe a preference for one over the other. The reaction tends to favor the pathway that forms the more stable carbanion. Unlike carbocations, carbanions are more stable when they are less substituted. The trend is primary more stable than secondary, which is more stable than tertiary. So in the classic Favorskii mechanism the ring opening usually proceeds in the direction that places the negative charge on the less substituted carbon. That gives the major product. This trend can break down in quasi-Favorskii mechanisms, where no discrete carbanion is formed, but for the usual enolate-based mechanism it is a good guideline.

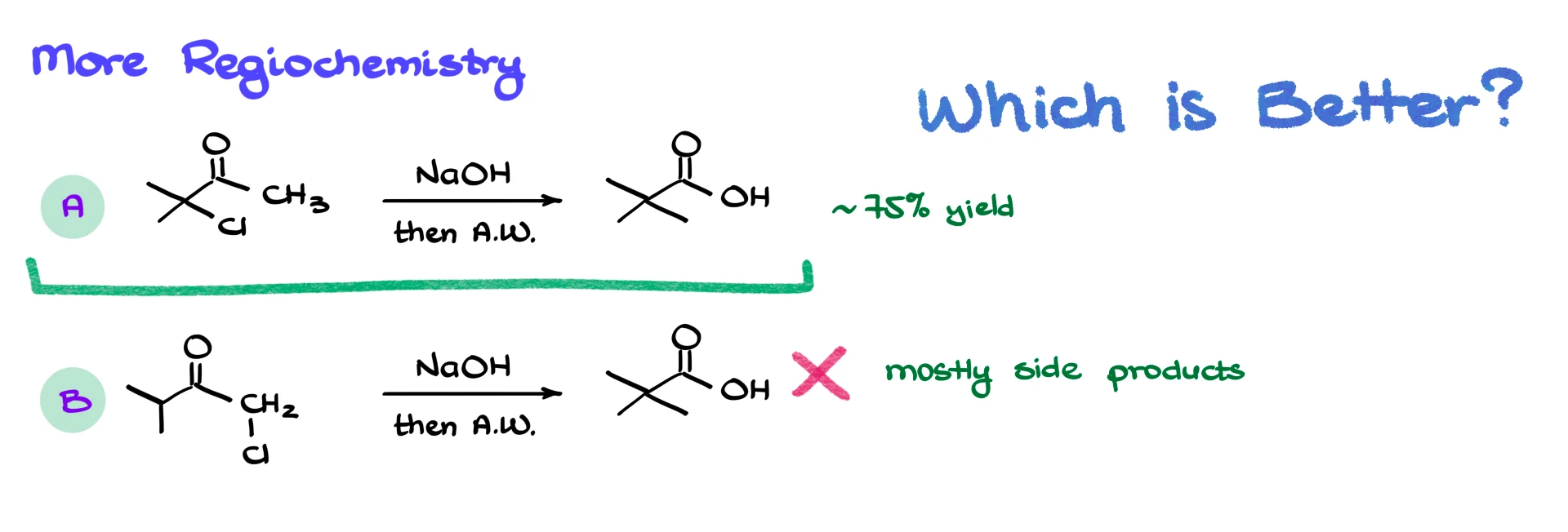

There is another interesting regiochemical question to consider.

Imagine two different starting materials that can both rearrange to give the same carboxylic acid. In one case the halide is on a more substituted carbon, in the other case it is on a less substituted carbon. Both routes converge on the same product. Which starting material gives the better yield?

Intuitively you might think the less substituted halide would behave better. However, experiments show that the substrate with the more substituted halide gives the better result, with yields around seventy five percent, while the other substrate gives mostly side products. The explanation lies in the enolization step. Enolization occurs more easily at less hindered positions, and in the more substituted halide substrate the α-position that actually needs to enolize is less sterically crowded. The fact that the halide carbon is tertiary does not cause serious trouble in this intramolecular SN2 step because three-membered ring formation bypasses many of the usual steric issues.

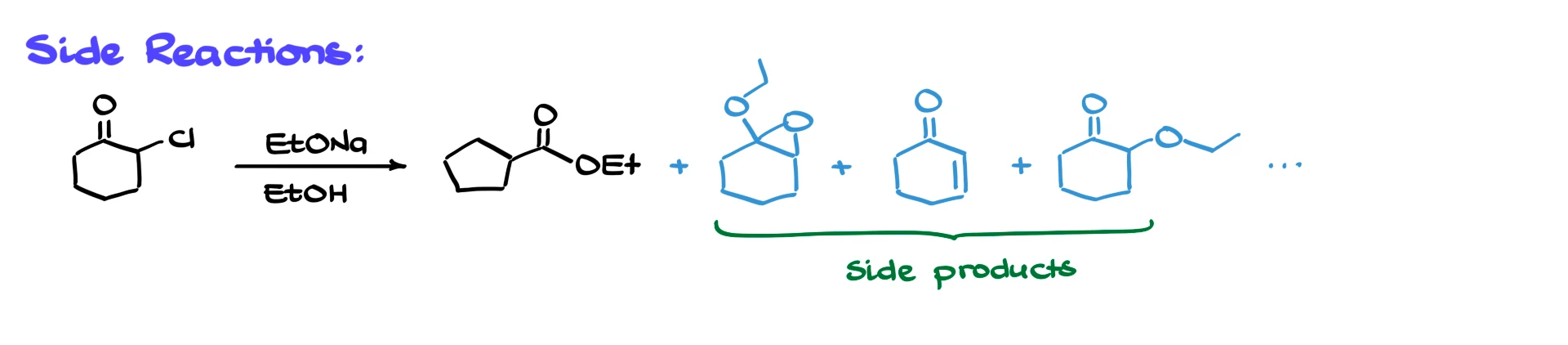

Side Products in Favorskii Rearrangement

Since we have mentioned side products, let us address them too.

If I go back to the original example of α-chlorocyclohexanone treated with sodium methoxide in an alcohol, the desired product is the ring-contracted ester, ethyl cyclopentanecarboxylate. However, the reaction can also produce side products such as epoxy ethers, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, simple substitution products and other minor species. In practice, though, if the reaction is done under optimized conditions, the rearranged product is still the major outcome. The classical transformation of α-chlorocyclohexanone to the corresponding ester is well documented and gives yields around sixty percent, which is quite respectable considering the complexity of the pathway.

Final Thoughts

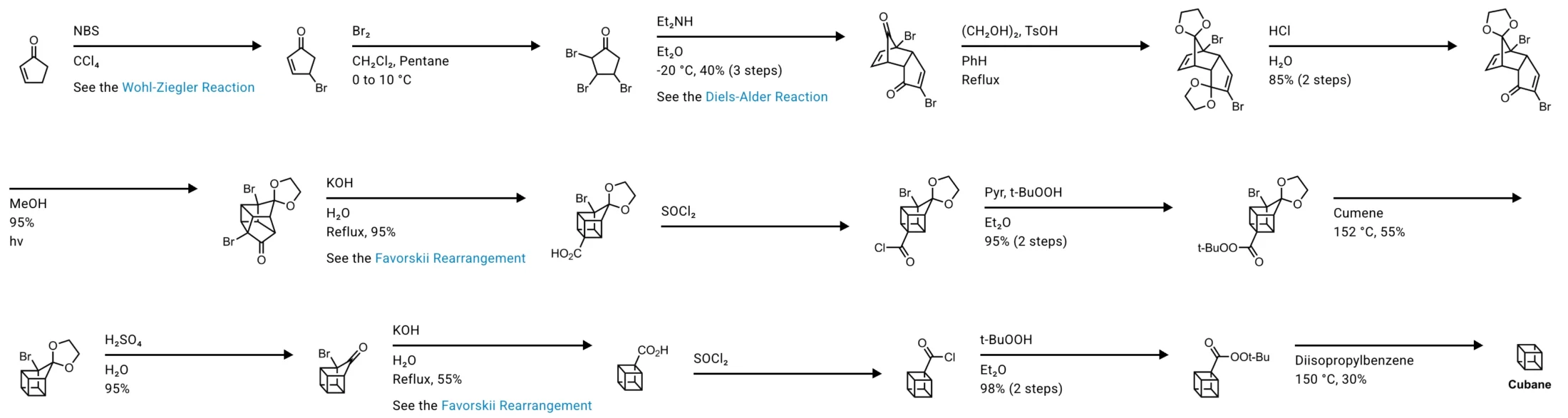

Historically, the Favorskii rearrangement has been used in some impressive total syntheses. For example, in the classical Eaton’s cubane synthesis syntheses, the Favorskii rearrangement appears more than once as a key step. In one case the yield for the Favorskii step is around ninety five percent, and in another case it is around fifty five percent, which is still acceptable for a single step in a long synthetic sequence. This should give you some confidence that the reaction is not just a curiosity on paper, it actually works in real molecules in real labs.

So to wrap up, the Favorskii rearrangement is a powerful and versatile rearrangement that lets you contract rings and rearrange acyclic skeletons through α-halogenated carbonyl intermediates. The classic mechanism goes through an enolate and a cyclopropanone, while special cases with small rings can use a quasi-Favorskii, benzylic-type pathway. Regiochemistry is governed by carbanion stability in the classic mechanism, and the reaction tolerates surprisingly substituted centers thanks to the geometry of three-membered ring formation.