Clemmensen Reduction

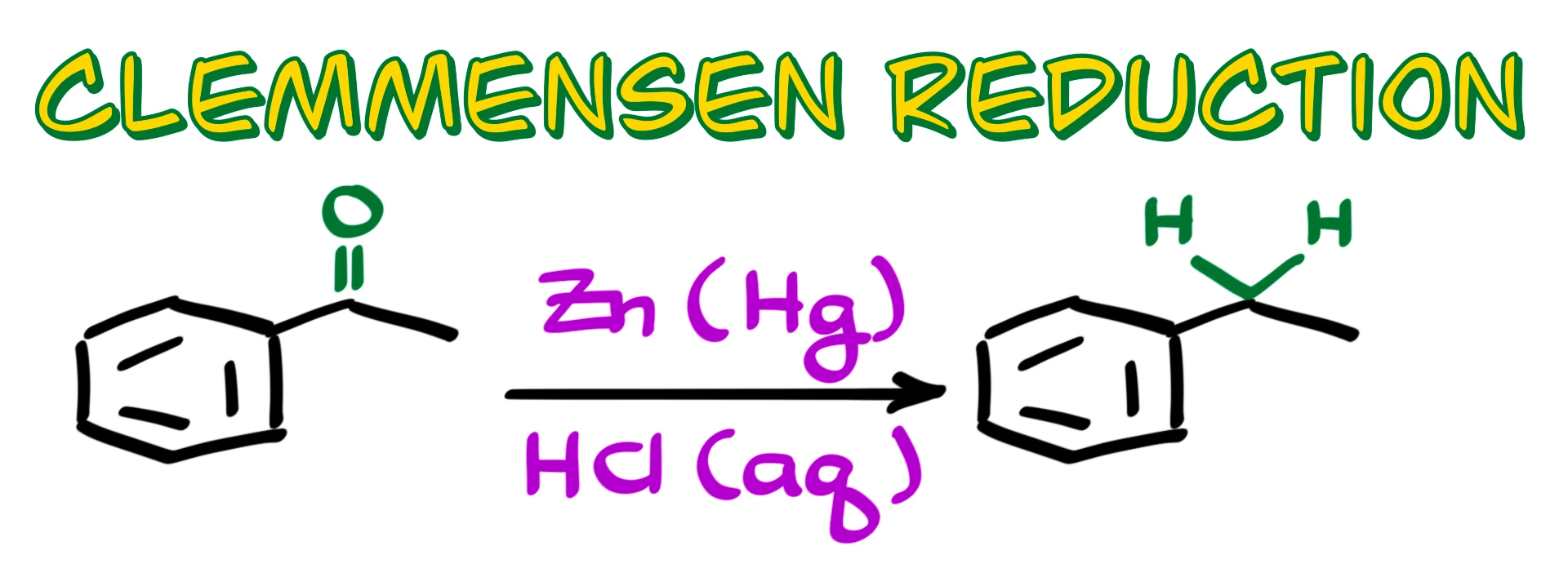

So when it comes to the Clemmensen reduction, pretty much every textbook, instructor, and tutorial out there will show you something like this: we start with a carbonyl compound, usually an aldehyde or a ketone, in my example a ketone, we treat it with zinc amalgam in the presence of hydrochloric acid, and as a result we completely reduce the carbonyl to a methylene group.

And if that is all you want to know about this reaction, good, you’re all set, and I’ll see you next time.

But if you actually want to know how this works, then pull up a chair, grab a cup of coffee, and let’s talk about it, because this is going to be a wild ride.

Clemmensen Reduction Mechanism

Let’s start with the mechanism.

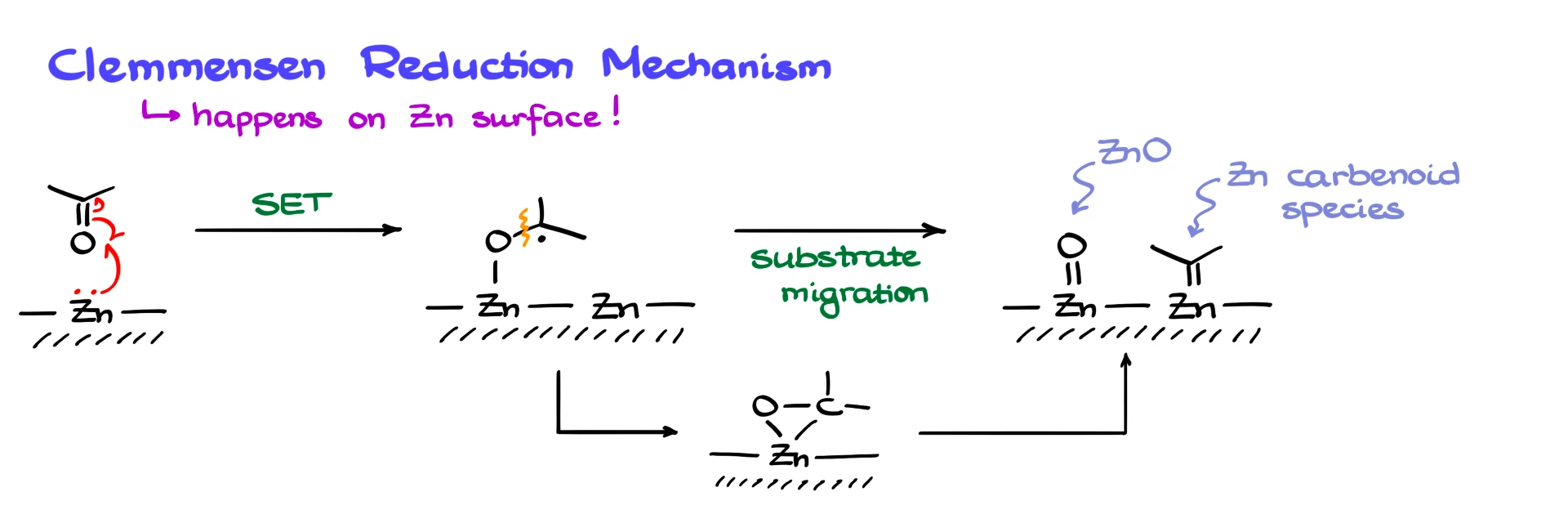

First of all, the reaction happens at the surface of zinc, so everything we discuss is occurring at the metal surface. I’ll represent the metal surface schematically, and for simplicity I’ll use acetone as my model carbonyl.

The most common mechanism you will see starts with a single electron transfer from zinc to the carbonyl oxygen. This forms a zinc–oxygen bond and generates a radical species. From there, the carbon–oxygen bond is proposed to break, and the carbon fragment migrates to another zinc atom, giving zinc oxide and a zinc–carbon species.

Another variation proposes formation of a three-membered ring involving zinc, which then fragments to zinc oxide and the organozinc intermediate.

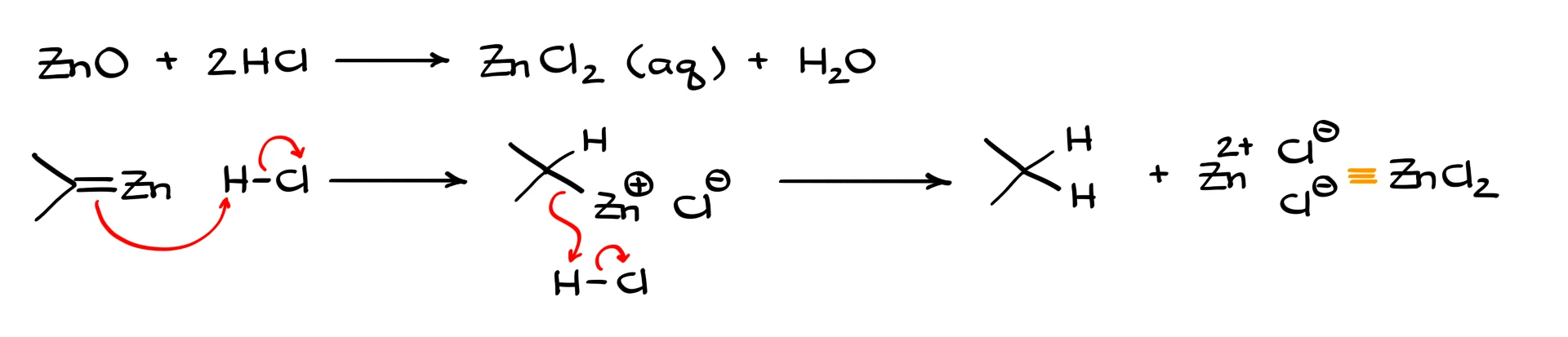

For simplicity, we separate those two parts. Zinc oxide reacts with hydrochloric acid to give aqueous zinc chloride and water. The organozinc species then reacts with HCl, gets protonated, and after two such protonations gives the fully reduced product along with ZnCl₂.

This is the most commonly shown mechanism. But do we actually have overwhelming evidence for it? Not at all. In fact, nearly every aspect of it is questionable.

Problems with the classic mechanism

Let’s break it down.

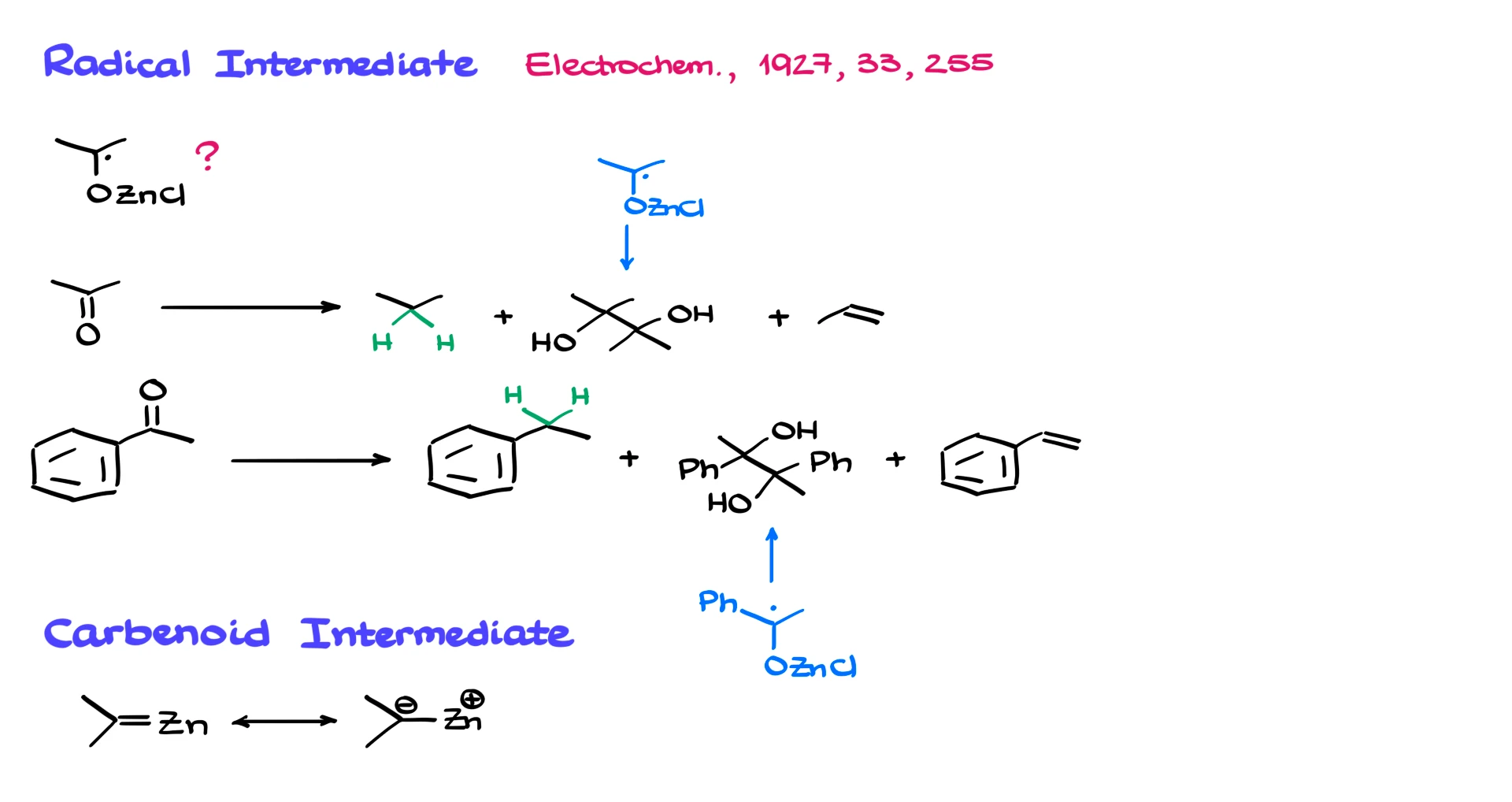

The radical intermediate was first proposed in 1927 in the Journal of Electrochemistry, and it has largely gone unchallenged. One of the reasons for proposing radicals is the formation of pinacol side products. For example, when acetone or acetophenone undergoes Clemmensen reduction, small amounts of the corresponding pinacol, a 1,2-diol, are often observed. That suggests radical recombination.

Since many reactions involving metals proceed through single electron transfer, the radical idea seems reasonable.

However, there is a serious problem.

A very common and often abundant side product of the Clemmensen reduction is the corresponding alkene. There is no reasonable way to generate alkenes directly from the radical intermediate that has been proposed. In some cases, alkene formation is so extensive that polymerization occurs and you end up with tar instead of your desired product.

So the radical mechanism cannot account for a major class of side products.

The next issue is the proposed carbenoid intermediate with a carbon–zinc double bond. For a true C=Zn double bond, we would need proper p-orbital overlap. Zinc is much larger than carbon, and such overlap is highly unrealistic.

Some have suggested that instead of a true double bond, we have a polarized structure with partial charges. But even that is problematic, because it would place excessive negative charge density on carbon. Carbon is not particularly good at supporting such high negative charge. So this intermediate is also questionable.

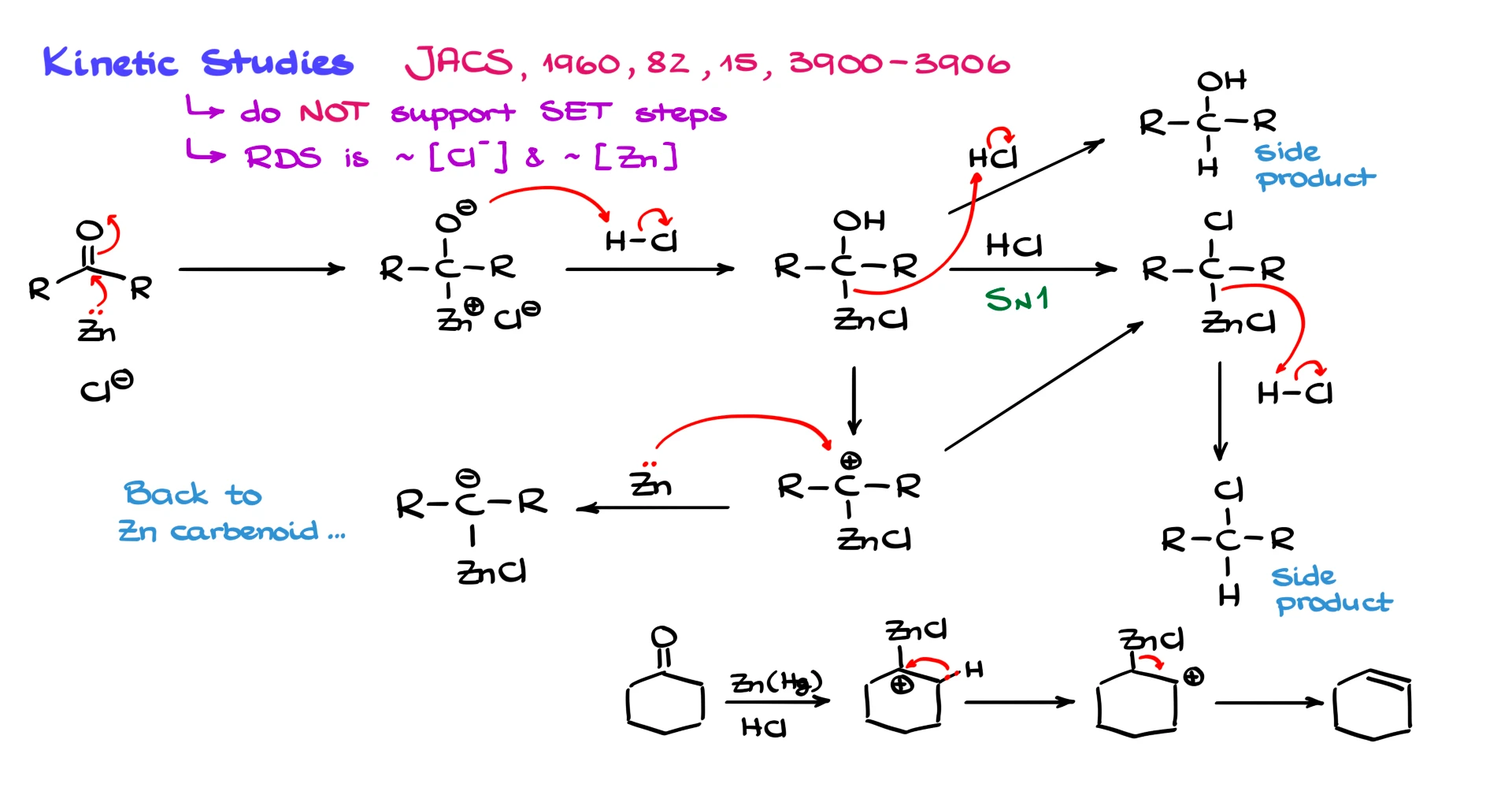

Kinetic Evidence Based Mechanism

Now let’s look at the kinetic evidence.

Several detailed kinetic studies have revealed two key observations. First, the data do not support a single electron transfer mechanism as the dominant pathway. Second, the rate-determining step depends strongly on the concentration of chloride ion and the amount of zinc present.

That suggests an alternative mechanism.

Instead of single electron transfer, the evidence supports a two-electron transfer. Zinc donates an electron pair to the carbonyl, forming a zinc–carbon bond directly and generating an alkoxide intermediate. Chloride appears to assist by coordinating and bringing the carbonyl and zinc together.

The alkoxide is then protonated by HCl to give an intermediate bearing both an –OH group and a zinc–carbon bond.

From here, several well-documented side reactions can occur.

One possibility is simple protonation of the organozinc intermediate by HCl, giving the corresponding alcohol as a side product.

Another pathway involves protonation of the –OH group, loss of water, and formation of a carbocation. That carbocation can react with chloride to give alkyl chlorides, which are indeed observed as side products.

The existence of carbocations also explains rearrangements. If carbocations are formed, we should see hydride shifts and skeletal rearrangements, and we do.

For example, if we start with cyclohexanone, we can form a carbocation intermediate. A hydride shift can occur, generating a more stable carbocation, followed by elimination to give an alkene. This accounts for the alkene side products that the radical mechanism cannot explain.

To complete the reduction, another equivalent of zinc can transfer two electrons to the carbocation, generating a carbanion-like intermediate. From there, protonation gives the fully reduced alkane.

I still have reservations about describing this species as a simple carbenoid. It may be more realistic to imagine a cluster of zinc atoms coordinating multiple organic fragments, similar to organolithium aggregates. Unfortunately, there is limited modern research on the detailed structure of these intermediates.

So which mechanism is correct?

Based on the literature, both pathways appear to operate. The dominant mechanism under typical conditions is ionic and carbocation-based. However, radical processes also occur as minor competing pathways.

Interestingly, in zinc amalgam the mercury can facilitate single electron transfer. According to double electrode theory in electrochemistry, electrons flow between metals of different activity. Mercury may act as an electron-transfer mediator, allowing radical pathways to occur even without direct involvement of zinc in that step.

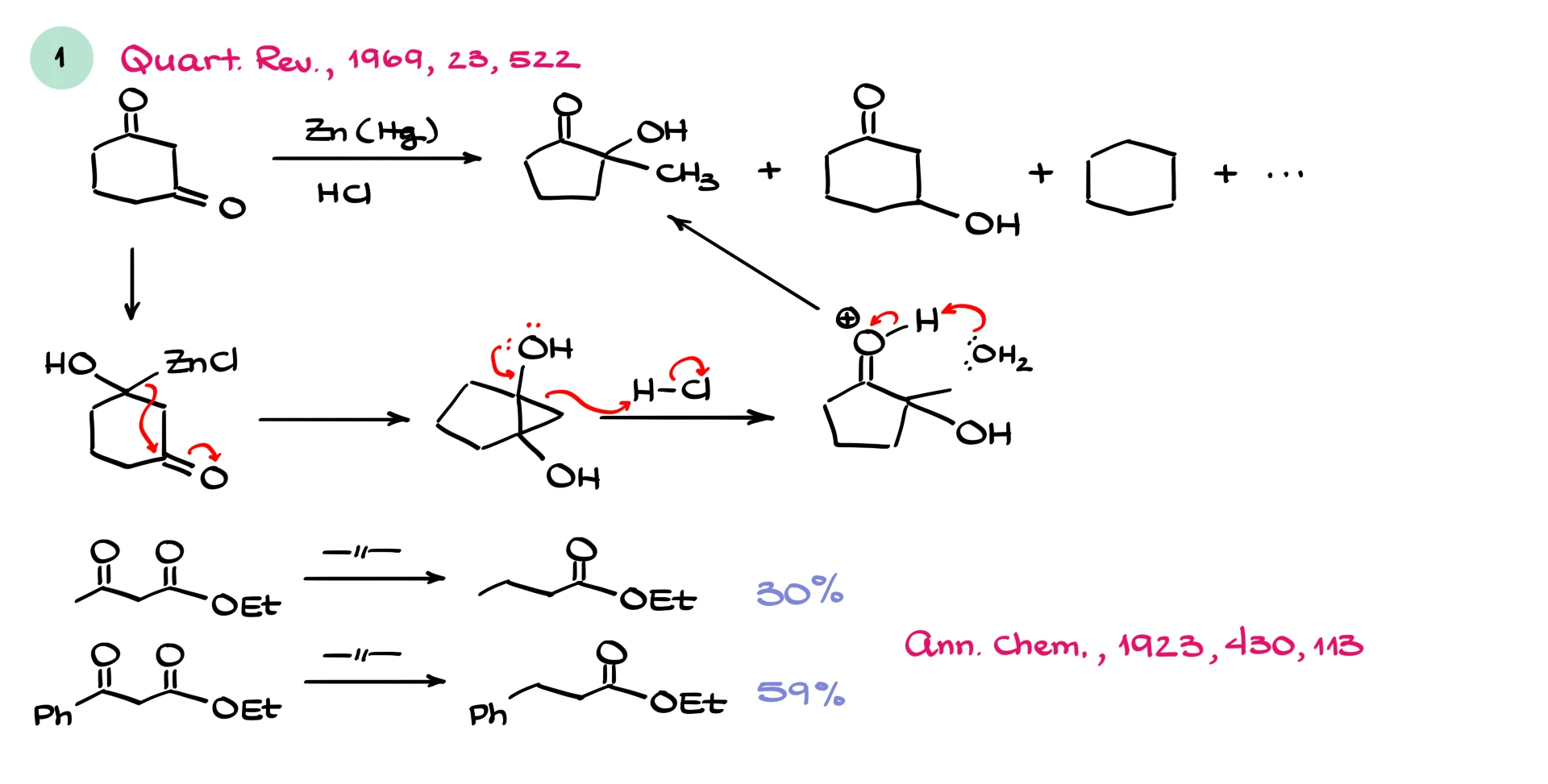

Clemmensen Reduction Examples

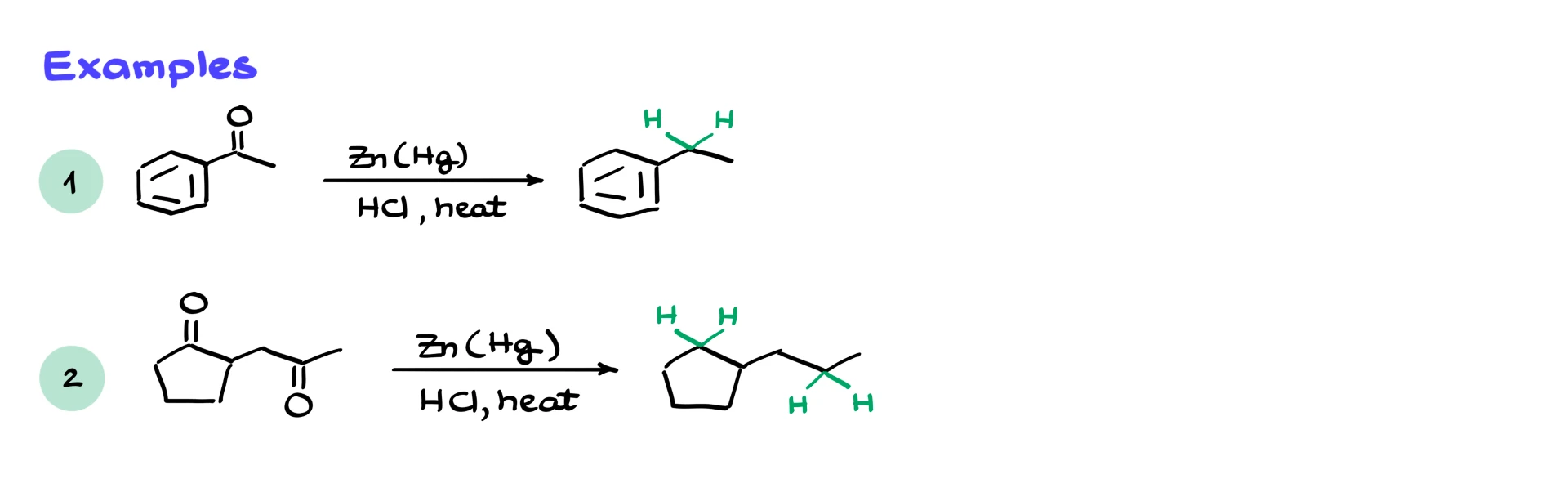

From a practical standpoint, though, we usually get the reduction we want. For example, acetophenone is converted primarily to ethylbenzene, with some side products.

If we have a molecule with multiple carbonyl groups, Clemmensen reduction can reduce them all, provided they survive the harsh conditions.

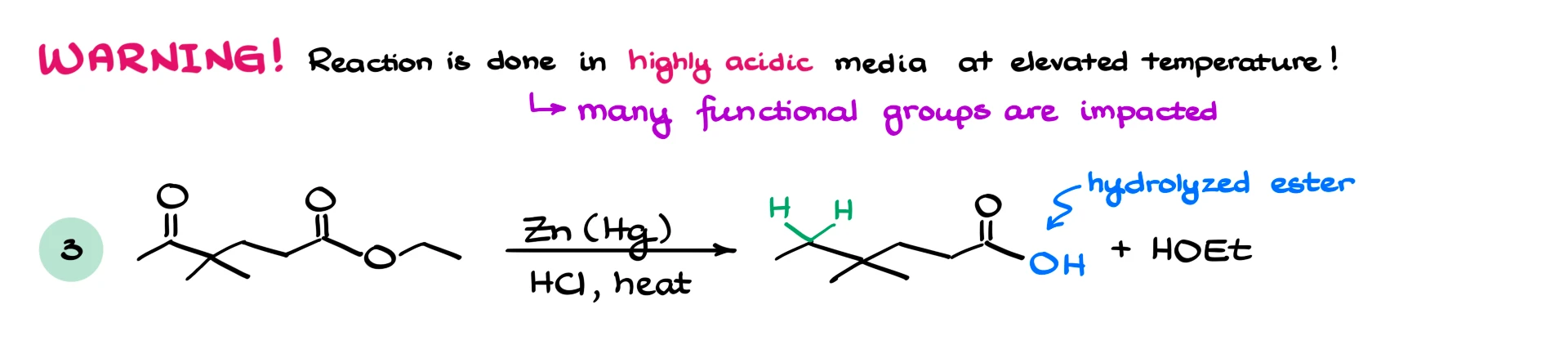

And those conditions are harsh. We typically use around 40 percent hydrochloric acid, essentially the most concentrated aqueous HCl available, and elevated temperatures. Any acid-sensitive functional groups may be affected. Esters, for example, can hydrolyze under these conditions.

Solubility is another consideration. The reaction is performed in aqueous media, so large hydrophobic molecules may react poorly unless they contain polar functional groups.

Unexpected Reactions During Clemmensen Reduction

Now let’s look at cases where things go very wrong.

Consider 1,3-cyclohexanedione. In addition to forming cyclohexane, this reaction can generate significant amounts of side products. The organozinc intermediate formed at one carbonyl can attack the other carbonyl in the molecule, leading to ring opening and unexpected products. In some cases, these side products dominate over the desired product.

Not all 1,3-dicarbonyls behave this way. Beta-keto esters often reduce more cleanly.

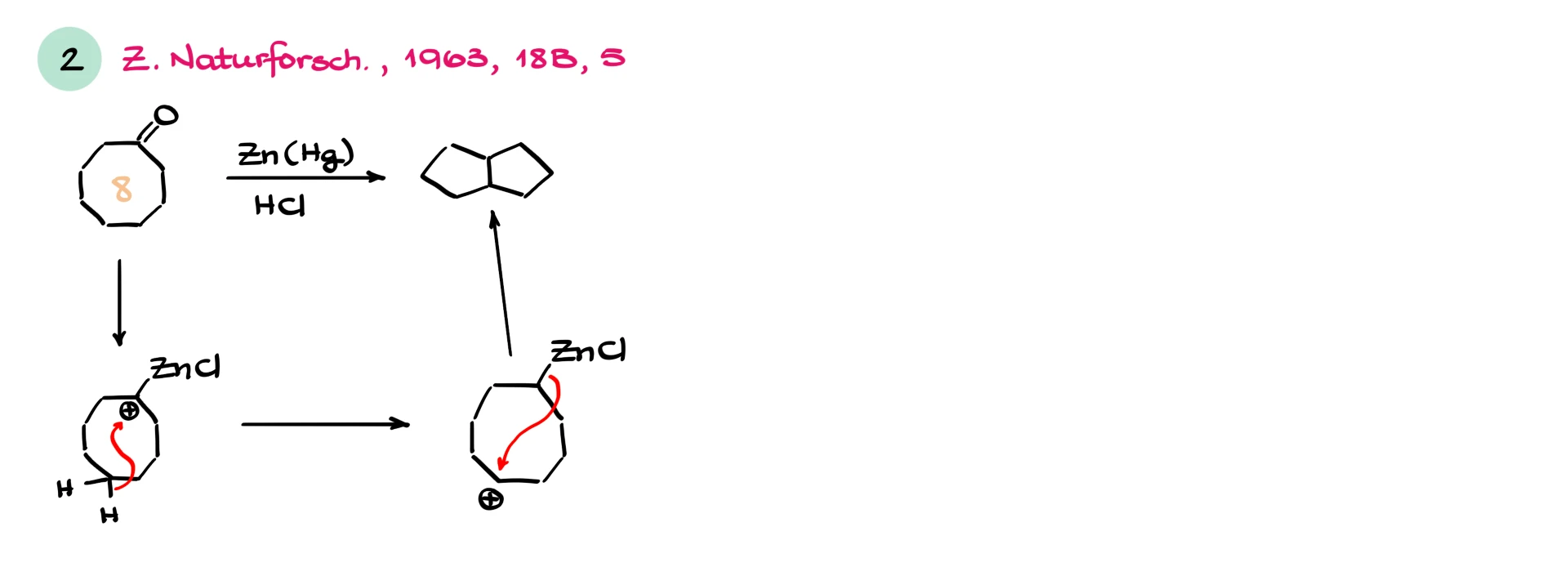

Another fascinating case involves transannular rearrangements. For example, cyclooctanone under Clemmensen conditions can form bicyclic products. A carbocation forms, a hydride shift occurs across the ring, and then intramolecular attack leads to ring contraction or rearrangement. Large rings are especially prone to these surprises.

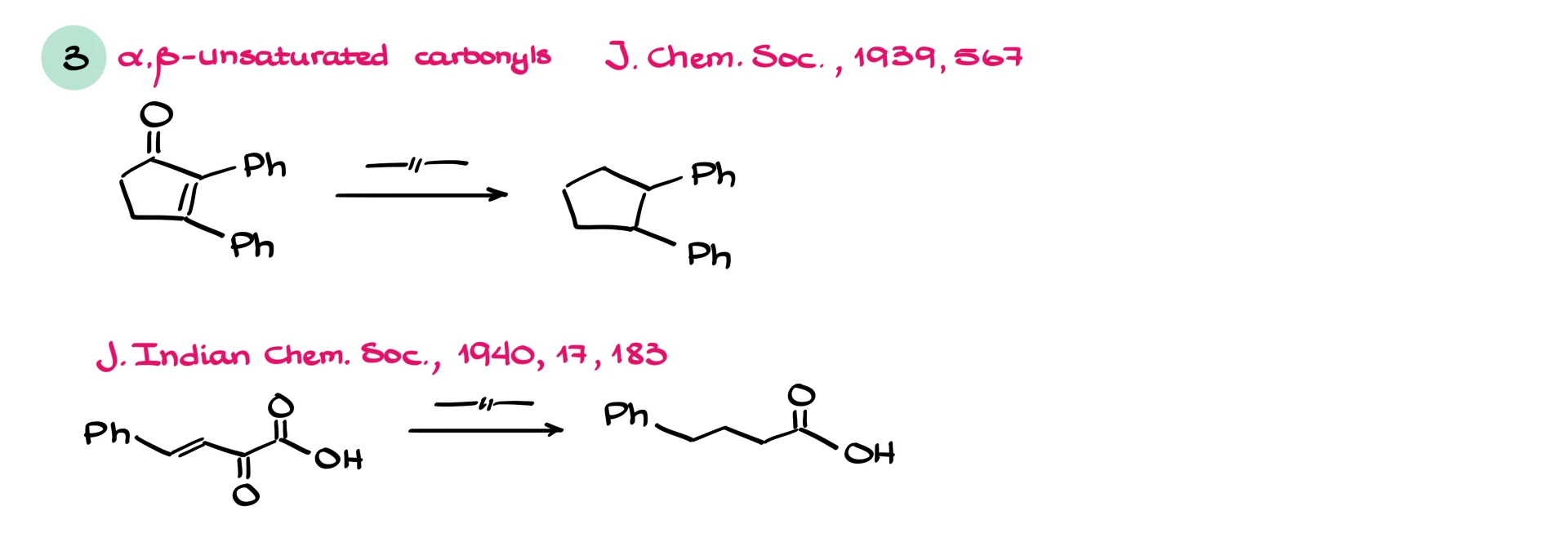

Surprisingly, ⍺,β-unsaturated carbonyls also behave differently. Under Clemmensen conditions, not only is the carbonyl reduced, but the double bond is often reduced as well. The major product is typically the fully saturated hydrocarbon.

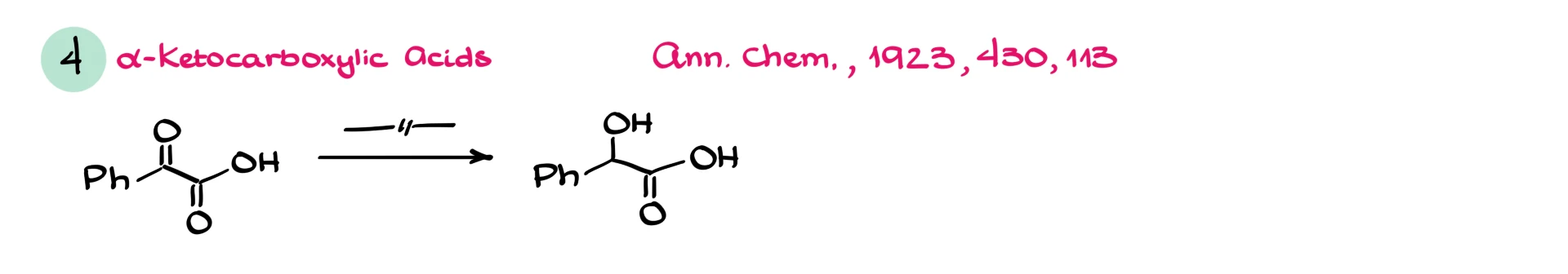

Finally, alpha-ketocarboxylic acids often stop at the alpha-hydroxy acid stage. Instead of complete deoxygenation, you retain the hydroxyl group. The reason for this selectivity is still not fully understood.

So what do you think about the Clemmensen reduction? Not bad for a reaction that textbooks often summarize in a single paragraph, right?

Which part surprised you the most? Let me know in the comments below.